Chapter 3: The Rescuer of Spirt

In the previous chapter, I have attempted to reconstruct the core of Girard’s psychology: acquisitive mimesis. Every instance of mimetic desire, I suggest, can be located between these three poles: from physical to metaphysical desire, from internal to external mediation, and from the positive to the negative phase.

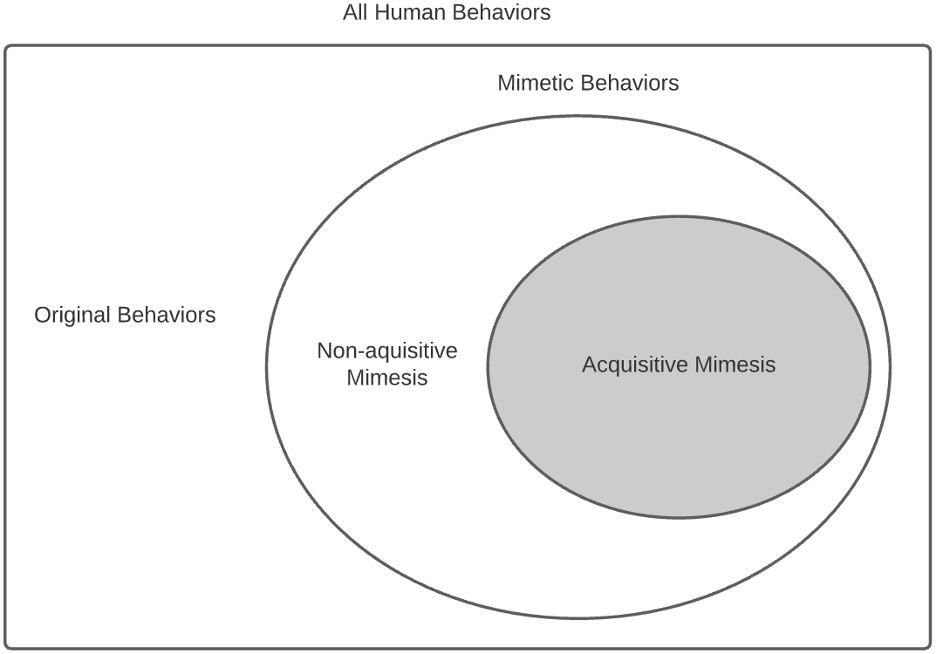

I have also, in the first chapter, illuminated the shape of what Girard chose to systematically leave out of his psychological picture. Within mimetic behavior, the exhaustive complement to acquisitive mimesis is non-acquisitive mimesis which plays a limited role in Girard’s system. Even more limited still is the role played by, what I termed, original behaviors which form the exhaustive complement to mimetic behaviors.

By emphasizing an overlooked species of desire, I hope to have defended Girard’s plausibility and, by putting him in dialogue with Rousseau, his originality. Yet, one last defense must be made. Even if mimetic theory is plausible and original, why is it significant? Why does this picture of human psychology deserve contemporary attention? My argument is going to be that mimetic psychology illuminates and rescues a part of human nature that has been systematically overlooked by popular currents within modernity. To accomplish this task, we must first interrogate Plato for resources to transcend our modern biases.

3.1 Tripartition

Plato famously offers a tripartite theory of the soul.[1] As the name suggests, Plato believes that there are three distinct components within human nature – reason, appetite, and spirit – each with their own means and ends. We have an appetitive part of the soul because we are embodied in animal bodies programmed to survive.[2] Its end is physical self-preservation and all the necessities – food, housing, security, sex, etc. – which survival demands. The appetitive part of the soul pursues these ends with the means of instinct – natural tendencies which evaluate things based on an immediate, instinctual criterion. That is to say when my instinct urges me to, for example, look for food, I judge which objects will satisfy me not by appealing to some distant, impersonal metric such as macronutrient content but by what I am immediately craving. Reason – the means of the rational part of the soul – on the other hand, evaluates things based on a mediated, normative criterion. Reason can step outside our embodied experience and make judgements based on standards that transcend our immediate inclinations. As the example of evaluating food on their macronutrient content suffices to show, reason can (and, for Plato, should) direct the other parts of the soul. But that is not to say that it has no end of its own – the rational part of the soul is aimed at the end of truth and contemplative joy.[3] Finally, the spirited part of the soul pursues the end of social-standing – or, framed in contrast against appetite – social self-preservation.[4] To further delineate the ends of spirit from those of appetite, it is helpful to consider Achilles’ decision in The Illiad:

Either,

if I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans,

my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting;

but if I return home to the beloved land of my fathers,

the excellence of my glory is gone, but there will be a long life

left for me, and my end in death will not come to me quickly.[5]

Burdened with divine foresight, Achilles knows that his glory will have to come at the expense of his life and vice versa. Effectively, he is deciding between the end of spirit and appetite: the existence of his social self or physical self. By ‘social self’ I refer to one’s self-conception, or, identity. The assumption here, of course, is that our self-conceptions and identities are inherently social in nature – this can only remain an assumption for now, but I will soon show how they are constituted socially in origin, confirmation, and content. Since the end of spirit is a social end then its means must also be a social means. It is unclear in Plato what this social means precisely is (I will go on to argue that mimesis is a good candidate) but it is evident that it is a mechanism through which a significant dimension of our selves is constituted socially.

3.2 Utility-Calculating Machines

With Plato’s picture of the soul in view, I will go on to claim that an influential strand of modern thought systematically ignores the end and means of spirit – reducing humans to, at their best, rational, utility-calculating machines who use the means of reason to satisfy the end of appetite. To do so, I will reconstruct a history of philosophy offered by Axel Honneth – a recognition theorist who is just as concerned that the social dimension of our selves has been overlooked.

The first stroke of Honneth’s history of philosophy begins with Plato’s pupil, Aristotle, and extends to the medieval Christian natural law theorists.[6] What defines these pre-modern thinkers – and what will soon stand in stark contrast to the radical break of modernity – is that they saw humans as fundamentally social creatures. To put it in the Platonic terms that we have been developing, they recognize social means – the fact that our characters are constituted socially – and they legitimize the social end. That is to say, first, they acknowledge the possibility (if not necessity) that our identities, dispositions, and ends are formed by a social group. We can, for example, take on the habits of others and, importantly, take on a group’s ends as our own by identifying with the group. Second, they see certain forms of social participation as an end in-and-of-itself. An important species of good can only be won by being immersed in a community – the good in question is the act of participation itself, irreducible to the instrumental goods that participating may engender. The social ontology that results from this picture of human nature is not necessarily a collaborative one but one where subjects form deep relationships and attachments with each other and the larger community.

The departure from this picture of human nature as capable of (social means) and needing (social end) intimate social immersion begins with Machiavelli.[7] This break, for Honneth, lies in Machiavelli’s “conception of humans as egocentric beings with regard only for their own benefit” that underlies his political treatises.[8] Benefit here should be interpreted narrowly as self-preservation: our animal, appetitive end. This picture of human nature is a radical break because it ignores our social end – that there is a species of good that is not individual but communal in nature – and social means – that our identity may be shaped by and intimately attached to others. Alongside this reduced view of human nature, is a radical social ontology of “a permanent state of hostile competition between subjects” that amounts to a “perpetual struggle for self-preservation.”[9] Under this light, the only relationships subjects can establish with each other and the community at large are shallow and instrumental ones that matter only in so far as they relate to one’s own interests.

If Machiavelli was the one to inject this intuition into the philosophical canon, then Hobbes – Honneth’s history continues – was the thinker who established a justification of the state upon this reduced view of human nature and antagonistic social ontology. Hobbes attempts to legitimize the sovereignty of the state by imagining what a state of nature without one would be like. Starting from Machiavellian intuitions about human nature – as concerned primarily for one’s own self-preservation – Hobbes concludes that the natural state of relations between human subjects is an escalating war of all-against-all. Effectively, Hobbes uses the obvious undesirability of this state of nature to justify a social contract that limits the freedom of each subject and grants authoritative power to the state to manage the inherently antagonistic relations between individuals. Importantly, the reason that these hypothetical subjects would consent to such a contract is not out of a concern for the greater good or a desire for belonging but primarily out of a rational calculus of what is in their own best interest. Honneth comments: “Contractually regulated submission of all subjects to a sovereign ruling power is the only reasonable outcome of an instrumentally rational weighing of interests.”[10] So, it is only with Hobbes that the full picture of human nature, which I ascribed to influential currents within modern thought – humans as rational, utility calculating machines – comes into view. Hobbes confines the task of political philosophy to the rational obtainment of physical self-preservation or, in Platonic language, to use the means of reason to achieve the end of appetite. To be sure, Hobbes did not completely overlook the spirited part of the soul: one of the key motors in the war of all-against-all are subjects’ desires for glory. But this concern for social-standing only plays a relatively minor explanatory role and, more crucially, is given no normative weight. That is to say, the social contract and, eventually, the state do not gain their legitimacy from and have no responsibility towards resolving citizens’ spirited end but exclusively their appetitive ones.

Lest we draw the wrong conclusions of what is at stake in systematically overlooking spirit, I must add a third author to Honneth’s history of philosophy who operates on a similar view of human nature but reasons his way to a very different social ontology: Adam Smith. The extent to which Smith takes humans to be rational, utility-calculating machines can be seen in his inquiry into the origins of the division of labor. How did this complex social structure – touching upon most facets of life, encompassing a wide variety of normative relationships, and “from which so many advantages are derived” – arise?[11] It did not result from, so Smith argues, “human wisdom” which foresaw its benefits but from “the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.”[12] Smith takes this propensity of rational, self-interested calculation to be a constitutive capacity of humanity and, with it as the dominant if not exclusive logic, attempts to explain a wide array of social phenomena – the division of labor being one of them. We did not, this line of thinking would suggest, specialize in a single craft due to the directions of a village elder, out of the joy of mastery, a yearning for professional recognition, or a desire to share our unique gifts with the community but solely out of a calculus of self-interest: if I am better at making armor than I am at herding cattle, I will be able to optimize my supply of goods if I exclusively make armor and trade them for cattle.[13] This reduced view of human nature – as rational, utility calculating machines – takes on its most obvious form yet in Smith’s understanding of the economic subject, but it would be wrong to level the same charge against Smith as we had against Machiavelli and Hobbes of systematically ignoring spirit. After all, an intersubjective core lies at the foundations of Smith’s moral theory found in his Theory of Moral Sentiments. Instead, I am only making the more modest claim that in the realm of economics, Smith seems content in conceiving of subjects as only using their means of reason to satisfy their end of appetite. The social ontology that results from this reduced view is atomistic as it had been for Machiavelli and Hobbes: we enter into relationships (as economic actors) only in so far as they advance our own material interests. But, crucially, this atomism does not lead to permanent competition but optimized cooperation. Through the workings of the invisible hand, the pursuit of one’s own interest advances the interests of the whole. Private vice – what caused unending conflict for Machiavelli and Hobbes – leads instead to public virtue. My reason for introducing Smith is, thus, not to argue that he has fallen prey to the same oversight but to show how deeply this atomistic intuition is embedded into all facets of social theory and, more importantly, that this atomism does not necessarily lead to antagonism and can even engender a social ontology of cooperation.

I have painted over a long period with a broad stroke, being more uncharitable than I would have liked had our aims not been internal to Girard. I only hope to have sketched an illuminating figure that is at least revealing as it is unfair. But, even if this reduced view of human nature does not represent the most sophisticated understanding, it is still a worthy position to interrogate given how dominant it is in the popular psyche. We can see the popularity of this conception of humans as rational creatures primarily concerned with appetitive, material ends in how prominently GDP is used as a normative criterion to gauge a country’s progress. Even other normative standards such as justice have taken a rational, material bent – often measured through metrics such as the Gini coefficient which concerns itself exclusively with material inequality. More generally, one way to interpret the popular observation that modernity is “materialistic” is that we only have material, appetitive ends in view and have lost sight of the other species of good available to human subjects.

So, what precisely is at stake in systematically ignoring spirit? Or, to return to our motivating question: why would it be significant to rescue this part of the soul? The full significance of a psychology of spirit will show itself to lie in the importance and pervasiveness of the social phenomena which it alone makes intelligible and, thus, will take the rest of this project to reveal. But now, I will attempt a general answer. To first clear the ground: what is not at stake is the question of whether social relations are naturally competitive or cooperative. As my introduction of Smith hoped to show, one can reason from this atomistic view of human nature and arrive at a fundamentally cooperative social ontology. Inversely, as my suggestion of Achilles as the archetype of spirit reveals, a more intersubjective understanding of human nature does not guarantee a harmonious social ontology. In fact, spirit can ignite more violent, unwarranted, and pointless competition than appetite. One need only think of Achilles deforming Hector’s dead body – a symbolic act that had no consequence on Achilles’ self-preservation – to be convinced of this fact. Why might spirit intensify conflict? This is the question I had hoped to anticipate by describing the ends of spirit as “social self-preservation.” Spirit can engender more grotesque forms of conflict because a species of survival is on the line – specifically, the survival of our social self. This is a dimension of the self that is often more important to us than even the physical – as Achilles’ decision shows – and is thus a more powerful motivator. It also tends to be quite fragile, threatened by the most innocuous of symbolic gestures.

What is at stake in overlooking spirit, then, is twofold. First, a social theory grounded on a reduced view of human nature fails to grasp the severity, variety, and frequency which antagonism manifests between subjects. Such a theory which can only conceive of conflict as resulting from appetitive interests does not have the theoretical means to predict, explain, or resolve the most atrocious acts of violence and will, thus, be defenseless against them in reality. It has trouble explaining, for example, the irrational but all-too-common motives of subjects who gain satisfaction from sabotaging others while not advancing their own material interests in any obvious way. If the first point just outlined is that ignoring spirit underestimates the extent of human evil, then the second point is that it is deficient in guiding us towards the human good. Even worse, since what we are deprived of is an inherently social good – none other than a relation with others – we would lack the intellectual resources to achieve both the good life and the good community. The reduced view only permits us to form shallow, instrumental relationships that matter only in so far as they advance our own ends. This is because our physical selves are relatively fixed and can’t expand to encompass others: our appetites are intimately tied to and defined by our embodied, limited, and separate physical forms. Appetite alone does not provide us with a mechanism to directly relate to others and, as result, we can only relate to others in so far as they matter to our ends. The social self, on the other hand, has no such limitation. It can expand and encompass others, taking their ends as its own. I will soon pursue a systematic explanation of how this may be possible; now, I will only provide a relatable example to make concrete what is at stake. As a husband I consider my children and my wife as, in some deep sense, part of what constitutes my own social identity and, thus, pursue the family’s ends as my own. My social self, as a ‘husband,’ has direct and immediate reasons to pursue ends that are not limited to my physical self because constitutive to the identity of ‘husband’ are inherently social obligations and rewards. It would clearly be a deficient relationship and an unsatisfying existence if, say, I had no joy whatsoever in helping my children and did so only in so far as they wouldn’t interrupt my own pursuits. Without spirit, we are robbed of these substantive relations and condemned to alienation because we would only be able to conceive of others as impositions or, at best, tools.[14] At the same time, communities would amount to no more than a mob of atoms joined together by a precarious equilibrium of self-interest, subject to dissolution at a moment’s notice. What is at stake, then, in ignoring spirit is failing to achieve the complete good and, out of naivety, inviting radical evil. Thus, if I am able to show Girard to be a convincing candidate for rescuing spirit, I will have, at the same time, shown his significance to be in rationalizing our irrationalities – that is to say, making intelligible (rationalizing) the ways in which we are more than just rational, self-interested machines (our irrationalities). To this task, I now turn.

3.3 Social Animals

Completing this task amounts to showing that there are psychological resources within mimetic theory that are plausible candidates for the means and end of spirit. I will argue that mimesis satisfies the former and metaphysical autonomy, the latter.

Recall, the form of mimesis is constitutive to behavior which proceed when the subject calls to mind an externalized instance of said behavior. Borrowing resources from Hume, I described mimesis as a form of co-resonance. Mimesis, then, is a mechanism by which we gain access to others’ subjectivity or, put differently, the route by which we expand our subjectivity to encompass the experience of others – the type of expansion I identified as lacking for the physical self. It should not be a surprise then, prima facie, that I take this intersubjective pathway to underly all the ways in which we are social creatures and be a plausible candidate for the means of spirit – the mechanisms by which our identities and ends are constituted socially. Specifically, we have already traced three ways in which mimesis forms us socially which I will now reinterpret through the lens of spirit. First, metaphysical desire furnishes us with ends acquired from an external model. These new ends often carry with them new identities – if I have an intense desire to write, I naturally conceive of myself as a writer. In this case, our ends and identities are socially constituted by mimesis in the sense that their origins are social. Second, as I have deduced from our discourse with Rousseau, the fact that mimesis imbues actions with a degree of confidence leads us to seek recognition. To continue the analogy, it is only when others recognize me as a writer do I feel secure in my identity and ends. In this second way, our ends and identities are socially constituted by mimesis in the sense that their confirmation is social.

To be sure, these first two points only show mimesis to socially constitute us in a weak sense – the origin and confirmation of my identity may be social but its content can still be atomistic, concerned only about myself. So how does mimesis enable the stronger, more substantive sense of social constitution that I attributed to the husband where the very content of the identity contains within it social obligations that extend beyond the physical self? As I hoped to have emphasized through Hume, sympathy – the co-experience of an other’s subjective content – is a subset of mimetic behavior. Sympathy provides the psychological foundation for my taking an other’s ends as my own because I, through mimesis, experience their experience as my own. It might be helpful to think of a husband sympathizing with his sick wife: mimesis grants the husband direct access to the subjectivity of his wife which, in turn, prompts non-instrumental action. What I am suggesting is that whenever we take on a substantively social identity such as ‘husband’ we are, at the same time, encouraging ourselves to more frequently access the subjectivity of those we have obligations towards through mimesis. Because we are constantly mimetically conjoined with these specific others, experiencing their experiences, we have direct reasons to promote their ends. This explanation of how we take on a social identity – as an extension of our subjectivity – also captures what is so rewarding about social participation: it expands the scope of our social selves. In this third and stronger way, mimesis constitutes our identities and ends in the sense that their content is social and directed towards others. But, I must remind the reader, the fact that our identities can be so substantively conjoined with those of others is as much a precondition for envy and sabotage as it is for love and support. That is to say, just as our spirited selves can take the furthering of other’s ends as an end in-and-of-itself so can we take their thwarting. The pandora’s box that mimesis opens up is the social self which gains satisfaction in relation to others. This can be a harmonious relation as my example of the husband attempted show. But it can also be an antagonistic one where I take the very failure of my rival as an end in-and-of-itself. This is the fundamental logic of mimetic rivalry, which I have already traced, that operates on the mechanisms of mimesis and transference. Recall, contrasted against simple mediation (the first way in which mimesis constitutes us socially), the logic of mimetic rivalry is not just about acquiring the object to have the same being as the model, but to steal the object from the model robbing him of his elevated status in retributive vengeance. With the introduction of blame directed through transference, we take the thwarting of an other’s ends as a good in-and-of-itself. Put differently, just as the social self can expand to encompass ends that lie beyond its physical self, so can it be threatened by developments that do not encroach upon its material interests. For example, if I consider myself ‘the best lifter,’ meeting someone who lifts more than me would threatens the very survival of this identity even if it does not change my material existence. In the final analysis, this third and substantive way in which mimesis constitutes us socially is a mechanism for radical evil as it is for profound good – precisely the two extremes we had hoped to rescue in resurrecting spirit.

This resurrection is incomplete, however, until I can show that metaphysical autonomy is as convincing a candidate for the end of spirit as mimesis is for its means. Recall, I’ve described the end of spirit as either social self-preservation or, more practically, a concern for social standing. It may, at first glance, be difficult to see why either of these formulations are even translatable, much less equivalent, to metaphysical autonomy. After all, the first characteristic I attributed to metaphysical autonomy is that it is an ontological state that has to do with freedom and reality. This concern should be partially assuaged when taking into account the second characteristic I attributed to metaphysical autonomy: it is an ontological state that requires practical confirmation. Put more strongly, what we are really seeking is a social freedom – to not be dependent on others – and a social reality – to exist in great measure in the eyes of others. This idea should no longer be foreign given the many social mechanisms that I have examined – esteem, mediation, symbolic gestures, competition, etc. – which determines the allocation of metaphysical autonomy. But to fully resolve this concern, I must go beyond suggesting specific examples and will provide a general argument to square freedom and reality with social self-preservation and social standing. If one of the Girardian subject’s aims – reality – is to exist in great measure, it is natural to think that ‘great’ should extend along the temporal dimension. That is to say, when we aim to exist in great measure, we aim not only to be recognized as great momentarily but to ensure this recognition is preserved through time – hence, social self-preservation. And since the existence we seek is a social existence – reflected in the practical ways others relate to us – it is not contrived to describe this reality as a form of social standing. How does freedom fit in the picture? We can understand it as the content of what we want preserved through time, or, what we want to be recognized as. Put differently, the social-standing we want confirmed is the status of being free – not dependent on others. Under this light, the subject’s pursuit of metaphysical autonomy is a pursuit for freedom and struggle to have that freedom made socially real – that is to say, recognized by others. The Girardian subject is engaged in an intersubjective pursuit of freedom. It is helpful to think of Achilles’ desire for glory to see all of these elements at play. Glory is a social reality because it must be awarded by others; part of what makes it appealing is that it is preserved and can last longer than our physical selves; and when we are recognized as glorious, it confirms our ability to dominate others. This is a – granted, exaggerated and perverted – species of freedom because it takes the logic of independence to its extreme: it is not content with just being independent from others but is only satisfied if others are dependent upon it (dominated).

By arguing that the end of spirit can be meaningfully conceived of as a social confirmation of freedom – or, in Girardian terms – metaphysical autonomy, I hope to have completed my portrayal of Girard as a candidate for rescuing spirit and, thus, defended his significance in the broader canon as rationalizing humanity’s irrationalities. Spirit’s end is metaphysical autonomy and its means is mimesis; thus, the spirited part of the soul is none other than acquisitive mimesis, or, mimetic desire which encompasses all of ways in which we seek metaphysical autonomy through the means of mimesis. This view of Girard – as the rescuer of spirit – is, then, also productive in making sense of why he drew attention to the specific psychological elements that he had. What must have seemed like arbitrary decisions – to focus on mimetic instead of original behaviors and then to focus on acquisitive mimesis rather than non-acquisitive mimesis – becomes intelligible in the context of rescuing spirit: we focus on mimesis (the first split) because it is the means of spirit.

And we narrowed down to acquisitive mimesis (the second split) directed at metaphysical autonomy because it is the end of spirit.

Girardian theory concerns itself with the subject’s mimetic pursuit of metaphysical autonomy or, interpreted more generally, the intersubjective pursuit of freedom. This is not an arbitrary focus because, I hope to have shown, it encompasses the operations of spirit and reveals all the ways in which we are social animals instead of rational, utility-seeking machines. To make my conclusions more explicit, I am suggesting a strong identity between these different formulations: (1) the spirited part of Plato’s soul encompasses (2) all the ways in which we are social, spirited creatures and not just rational, utility calculating machines which is also the focus of (3) Girardian theory. Girard primarily concerns himself with the psychological mechanisms behind and the ethical, social consequences of (4) acquisitive mimesis, or, (5) mimetic desire which encompasses the ways by which (6) we use the means of mimesis to pursue the end of metaphysical autonomy or, put more generally, by which (7) the subject intersubjectively pursues freedom. The prime significance of Girardian theory is that it attempts to give an exhaustive account of what it means for us to be social, spirited creatures. But Girard’s significance goes beyond merely rescuing spirit. In all the numerous ways that I will now expound, Girard elevates spirit above appetite and reason and, as a result, fundamentally changes what we take humans to be while setting the stage for an equally radical social theory.

Spirit is elevated above appetite in two ways. First, the end of spirit tends to matter to us more than the end of appetite. Practically, this means that we often choose the former when the two are in conflict by, for example, eating at the less delicious but more prestigious restaurant. Second, spirit is elevated above appetite in the sense that what appear to be decisions made on the grounds of appetite are often attempts to satisfy spirit. We may believe that we chose a car because it is safe or a meal because it is delicious, but we often make these appetitive choices based on what they say about our social selves. Even stronger, Girard wants to say that we are almost always oblivious to the extent our spirited end directs us. This is because of the deceitful quality of metaphysical desire that I have already discussed: we believe the intense yearning we feel for the object is due to its inherent qualities and are completely unaware that its real origins lie in the metaphysical autonomy of the mediating model. In this second sense, spirit is elevated because it is the foundational criterion by which decisions are actually made, even if it does not appear to be so.

Spirit is also elevated above reason in three ways. First, reason is not strong enough to direct the force of spirit. I have already attempted to extract this assumption from Girard’s observation that politics cannot control wars motivated by a deep spirited hate[15], but there is more to be unearthed in this analogy. Not only is politics impotent at controlling these wars, often, these wars direct politics – that is to say, the fervor of war often transforms politics into a mere propaganda machine to justify violence. In like manner, reason is often a mere spokesperson for spirit: we decide on the grounds of spirit and reason’s only task is to make it seem as if we were moved by justifiable normative ends. So not only can reason not curtail spirit, but reason is also often spirit’s servant while pretending to be its steward. Practically, what I have in mind here are instances where, for example, we are attracted to a prestigious position for the sake of prestige yet justify our decision on other normative ends, say, doing good for society. Second, spirit is elevated above reason because reason cannot access spirit’s end. This can be interpreted as an expansion upon the ways in which reason has trouble curtailing spirit – if the first point is that spirit is often too strong, this second point is that spirit’s operations lie outside the dominion of reason. I’ve defined reason as the ability to evaluate based on a set of non-immediate, normative criteria or ends. For reason to successfully operate, then, it must be able to, as a minimal precondition, gain access to whatever ends motivating the subject. Yet, as I’ve already emphasized with appetite, spirit’s workings are hidden from us and not accessible – at least, not without considerable philosophical work. Thus, spirit is outside reason’s domain. If we take a narrower but quite common understanding of reason – as the ability to quantify based on a set of criteria – then the end of spirit is inaccessible in yet a further way: it defies quantification. It makes no sense to ask exactly ‘how much’ metaphysical autonomy we seek as it does for, say, the amount of food we want.

Before I proceed to the last point, I wish to first draw out the social significance of elevating spirit in the ways just discussed to begin advancing the second aim of this essay: to investigate how Girard’s psychological conclusions sets up his social theory. One important but not exhaustive consequence of promoting spirit (specifically over reason) is that it threatens all social theories grounded on rational political discourse: the intersubjective use of reason to arrive at some optimal agreement. Hobbes’ social contract is one such theory. Girard’s critique of Hobbes is that reason is most unavailable when it is most needed: during the war of all-against-all.[16] The idea here is this, when spirit’s end (metaphysical autonomy) is not inflamed during periods of peace, perhaps there is the possibility of people coming together and negotiating some kind of rational arrangement that would advance the interests of all. But at the height of an all-out war, what dominates subjects is a deep, spirited hate against others which reason can neither access nor control. It is unthinkable, for Girard, that opponents in such a war could just sit down, put aside their identity-constituting resentments, and negotiate some kind of optimal contract. Girard’s specific critique against Hobbes can be extended to all theories which rely on rational political discourse as such: people without significant training in specific nurturing circumstances, when participating in political discourse, do not use reason to access the standpoint of the common good. They do not even use reason to defend their own appetitive best interests (the hope being that if everyone did so, the group will converge to the common good). Instead, because of the dominance of spirit, what appears to be the outcome of reason, when people participate in political discourse, is more so an ex poste rationalization of spirit’s social demands. For the vast majority, reason is merely a spokesperson for spirit. This critique can be made more concrete if we were to consider how Girard would depict the democratic process. Girard would say that people do not choose their candidates based on whose policies advances the common interest. We do not even vote for candidates whose policies best advances our narrow self-interest. What the majority of us do, instead, is choose the candidate based on the social signals we want to give off and then rationalize why they are good for the common interest. More generally, Girard would observe, democratic citizens make national decisions – support movements, vote for candidates, pick political parties – to win local, social rewards. ‘Rewards’ does not imply conformity; recall, the negative phase of mediation promises to reward us if we pursue difference. In this case, we would appear to be making decisions independently through reason by deviating from the group but what we would really be doing is pursuing difference for difference’s sake. We would, for example, vote for an economically progressive candidate not out of reasoned analysis but from, say, a personal resentment of our richer peers. Seemingly contrarian decisions like these would still be pre-determined by our social relations and not by reason. Even worse, we would be oblivious to this fact due to the deceitfulness of mimesis. The idea that our rational opinions are actually determined by a social graph that is orthogonal to truth should not be foreign to the careful reader. After all, in our discussion of metaphysical desire, I have argued how our most intimate ends – what we consider to be the most valuable and rewarding pursuits – are determined by none other than this social graph. It is only natural to think then, our closely held political opinions are subject to the same force. To be sure, the picture I have attributed to Girard may appear to be too strong: we certainly have some access to reason and, furthermore, we are not always so spirited. Indeed, this is true: there are times when reason stewards spirit. Girard is trying to advance a more nuanced and, in some sense, even stronger view. He does not think rational political discourse is theoretically impossible, but that it requires a very specific and rare set of circumstances where subjects are not overly spirited and have strengthened their faculties of reason. But precisely when reason is needed the most – when democratic subjects are at each other’s throats, when there is a fundamental conflict of interest, when people see in the other a radical evil – is when spirit is inflamed and the circumstances for reason’s stewardship is thwarted. Put simply, people don’t rationally listen to each other when this form of communication would be most helpful. Rational political discourse is impotent because all it can resolve are trivial disputes – when little is on the line – in matters of great import, those that are intimate to our identity, reason becomes a mere mouthpiece for spirited allegiances and resentment. Making matters worse, the direction of Girard’s history, for reasons that will only become apparent in Girard’s social theory, is increasingly hostile to the already rare circumstances that allow for reason’s stewardship, rendering rational political discourse a practical impossibility.

As if this did not already present a strong enough challenge, the third and last way in which spirit is elevated above reason strikes an even more devastating blow to our modern intuitions: spirit evolutionarily precedes reason. The point I have in mind cannot be found internally within Girard but can be easily transplanted from Rousseau to Girard. Rousseau argued that amour propre – the desire for esteem – is evolutionarily[17] prior to reason because of two unique qualities of the former. First, amour propre forces us to go outside of ourselves and examine ourselves from the perspective of those from whom we hope to win esteem. It is evolutionarily prior, because without this impulse, there is little cause for us to go beyond our first-person, solipsistic perspectives. At the very least, the use of amour propre strengthens our capacity to not render judgement from our immediate ends and, instead, externalize ourselves – a pathway that reason must take as well. Second, because it is esteem – normative approval – that we seek, the external position we inhabit is also a normative one (instead of, say, putting oneself in the perspective of one’s prey to determine their orientation in order to hunt them). Thus, amour propre trains us not only to abstract away from our immediate ends and access an external position, but also to inhabit an external position whose normative attitude and ends are different than our own – precisely the position that reason must also be able to access. The basic idea here is that we need to be able to ask the question “does he think this is good?” (amour propre) before being able to ask the more abstract question “is this good?” (reason).[18] This line of argumentation can be easily transplanted to Girard. First, if reason is the capacity to evaluate on non-immediate criteria, then it must be dependent on a more fundamental capacity for us to escape our immediate perspectives. I have argued that mimesis is the pathway by which we expand our subjectivity to access external positions. Second, reason needs to access a specific type of external perspective, namely, a normative one. This is precisely what Girardian psychology focuses on with its emphasis on acquisitive mimesis – the acquisition of not just others’ habits or appearances but their normative attitudes and ends. The argument I am trying to make is that without the capacity of acquisitive mimesis – the ability to gain access to and acquire external, normative perspectives – humanity will not have been able to develop its capacity for reason. But even if this is factually true, why does this particular mode of precedence matter? After all, we have already evolved, and reason can, to a certain degree, operate independently of spirit even if the former was, at some time in the past, evolutionarily made possible by the latter. It matters because histories determine how we think about the present and this genealogy, in particular, challenges what we take humans fundamentally to be. A popular line of thinking, offered by philosophers such as Aristotle, identify the constitutive capacity of humanity to be reason. The evolutionary story we have been trying to paint suggests otherwise: reason may be a constitutive capacity of humanity but it is only made possible by the constitutive capacity of humanity: acquisitive mimesis. To think that humans are defined by reason would be like thinking that fire is defined by smoke and not flame – mistaking a unique quality derived from and dependent upon its essence as the essence itself. Indeed, Girard describes the process of hominization – the evolution from animal to man – as none other than the strengthening of acquisitive mimesis.[19] In a Rousseauian move, we add to Girard that even that which we pride ourselves most with – reason – is but a mere side product of this more fundamental development. Under this light, humans are not reality-seeking but myth-making animals; not independent but mimetically-bound creatures. Put more provocatively, our essence – what really defines us – is not the yearning for truth, but the ability to believe in lies as long as others do as well.

3.4 The Shape of Girard’s Social Theory

This radical view of human nature sets the foundations for an equally radical social theory – one where groups can only be reconciled through lies and violence, where truth brings war not peace, and where the historical expansion of justice, equality, and transparency begets apocalypse. While the explanations of these specific social conclusions are beyond the reach of Girard’s psychology, I will now turn completely to the second aim of Part One and discuss how the psychological resources we have unearthed helps us understand and situate mimetic social theory. As is the case with his psychological landscape, Girard’s social theory is partial in two ways. First, it is partial in that it only concerns itself with the social operations of spirit, or, acquisitive mimesis. That is to say, he will not be interested in, say, how we can facilitate rational political discourse or how to systematically address the appetitive ends of all. This should come as no surprise given that the only psychological resources that Girard has at his disposal are those of spirit. Second, within the social operations of spirit, Girard is interested in a partial subset: the pathologies that result when spirit is inevitably upset in its mimetic pursuit of metaphysical autonomy. It is important to keep these two partialities in mind lest we think Girard’s social analysis – such as scapegoating – exhaust all there is to be said about society. Instead, they should be read as social pathologies which result when a large group of people fail in the mimetic pursuits of metaphysical autonomy – or, framed differently – their intersubjective pursuits of freedom.

Framed in this second formulation, it may be helpful to think of Girard as the negative complement to Hegel. In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel attempts to answer the question: what does a social order that systematically satisfies all its citizens’ intersubjective pursuits of freedom look like? Girardian social theory, on the other hand, answers a different, negative question: what happens when citizens intersubjective pursuits of freedom are thwarted?[20] Lest I trivialize Girard’s project it is important to see him as first answering “such a social order is impossible” to the Hegelian question. The concern of trivialization I am trying to assuage is the thought that Girard’s social theory only deals with accidental instances of social pathologies. Instead, his claims are more ambitious, systematic, and pessimistic: he will go on to identify mechanisms that, with the certainty of Newtonian laws, will bring about these social pathologies. Even worse, the direction of history only exacerbates these mechanisms until they eventually lead us to our inevitable apocalypse. Interestingly, what will make Girard a challenging and rewarding interlocutor for the Hegelian social theorist is that Girard, very broadly, agrees with Hegel’s account of the direction of history: the expansion of transparency, justice, and equality. But what Hegel took to be the preconditions for actualizing freedom, Girard will see as the systematic blockers that prevent its realization. Thus, as is the case with his psychology, the partiality of Girard’s social theory is not unwarranted: we are at an eschatological time in history where the dominant logic of society is, increasingly, the pathologies which result from the systematic obstructions of freedom.

I have answered the question: “how does Girard’s psychology help us situate his social theory?” But what about the converse question: is there any aspect of his social theory that enriches our understanding of his psychology? Of course, there are too many possible answers here; but one in particular stands out in my attempt to portray Girard as the rescuer of spirit. We have been using spirit as ‘spirited,’ relating to the social. Yet, there is another sense of spirit – as ‘spiritual,’ relating to religion, sacrality, and divinity – that is equally apt for mimetic theory. We will go on to find, in Girard’s social theory, that it is none other than the psychological mechanisms we have covered within acquisitive mimesis – shame, transference, mimesis – that gives rise to religions and gods. Girard, then, rescues spirit in a second sense by creating a grammar for the sacred. Furthermore, by showing us to be religious creatures through the same mechanisms that make us social creatures, Girard establishes a fundamental identity between these seemingly unrelated spheres: all religious phenomena are social in nature and, conversely, all social phenomena have a religious dimension.

Girard rescues spirit – hidden since the foundation of the modern world – in all its richness: the good and the evil, the sacred and the profane.

Footnotes

[1] For a modern reconstruction see Burnyeat, Tripartition.

[2] For a more detailed reconstruction of the appetitive part of the soul see Burnyeat, Tripartition, 8.

[3] For a more detailed reconstruction of the appetitive part of the soul see Burnyeat, Tripartition, 13.

[4] For a more detailed reconstruction of the spirited part of the soul see Burnyeat, Tripartition, 9.

[5] Homer, Illiad, 9.411 – 416.

[6] See Honneth, Struggle, 7.

[7] See Honneth, Struggle, 8.

[8] Honneth, Struggle, 8.

[9] Honneth, Struggle, 8.

[10] Honneth, Struggle, 10.

[11] Smith, Nations, 29.

[12] Smith, Nations, 29.

[13] See Smith, Nations, 31.

[14] For a close approximation of the species of good people would be deprived of see Neuhouser, Hegel, Chapter 3.

[15] Girard suggests that the more war becomes motivated by fervent hate, the less politics is able to control war. See Girard, Battling, 37 – 40.

[16] See Girard, Battling, 68.

[17] I use ‘evolutionarily’ because Rousseau seems to suggest, in his Second Discourse, that Amour Propre is a capacity lacking in the raw state of nature and develops only when we start living in communities. But since this state of nature is fictitious, it is unclear if ‘evolution’ is the right term to describe the type of precedence Amour Propre has over reason. Perhaps, ‘developmentally preceding’ is just as apt.

[18] For a reconstruction of the relationship between amour propre and rationality, see Neuhouser, Rousseau, Chapter 7.

[19] See Girard, Things, 90.

[20] The move I am suggesting to square Hegel with Girard is very similar to the move that Honneth uses in Recgonition, Chapter 5 to square Hegel with Rousseau: the latter describes the pathologies that result when the conditions outlined by the former are not met. Given Rousseau’s proximity with Girard, as I have already argued, it shouldn’t be a surprise that I assigned Girard a similar relationship with Hegel as Honneth did Rousseau.

Table of Contents

Part I: The Psychology of Spirit

Chapter 2: Acquisitive Mimesis

Chapter 3: The Rescuer of Spirit

Part II: A History of Violence

Chapter 4: Mimetic Anthropology

Chapter 6: Mimetic Eschatology

PART III: Antidotes to Apocalypse

Chapter 7: Renouncing Violence