These book notes on Debt are separated into two parts. The first part is a short summary of the book.

The second part is a reconstruction of each individual chapter.

Part I: Summary

Graeber cherry-picks his data (some of which are factually wrong) to paint a daring yet distorted picture of economic history that is illuminating as it is biased.

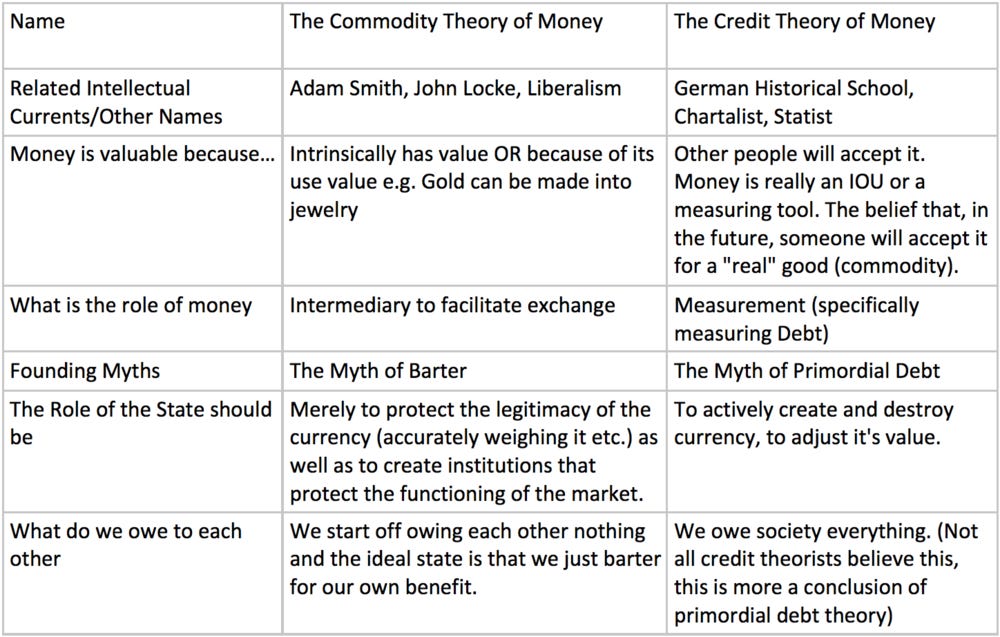

His project, in the first four chapters, is to dismantle two popular economic ontologies.

He first (Chapter 2) outlines the liberal/capitalist theory of Adam Smith, suggesting that Smith falsely identifies the logic of “barter” as the constitutive human capacity to justify the market and establish economics as a discipline. What’s wrong with Smith, in Graeber’s view, is that the history he depicts (Barter > Money > Credit) happened exactly in the reverse! Pre-money societies weren’t dominated by barter as so much by neighbors keeping tabs on the goods they give to each other in aid (credit). On the historical stage, credit was the first mode of economic behavior, and it was only until after money came on the stage did people begin bartering when money was not available to them.

Next (Chapter 3), he moves on to the socialist/primordial debt theory of money. If Adam Smith assumed that we don’t owe any debts to anybody to begin with (freely trading agents), then this alternative theory assumes the opposite: humans start off with infinite debt to the cosmos. As proof, these theorists cite how religions are often framed in the language of debt. They further claim that the government inherits the right to this primordial debt – this naturally leads to a socialistic logic where the government has total control over money and the market. The critique that Graeber levels against these theorists is immanent: he shows that religious debt (debt towards the cosmos/God) and moral debt (obligations towards one’s family/society) is fundamentally different from the logic of economic debt.

In Chapter 4, Graeber gives his definition of money. Money is both a commodity (Smith) as well as an IOU (primordial debt). He goes on to reject the liberal ontologies of both liberal and socialist traditions. Drawing upon Nietzsche, Graeber shows that the liberal tradition (we don’t owe anyone anything) and the socialist tradition (we owe everyone everything) stems from the same false assumption: they take reciprocity to be the only logic that governs social relations. That is why both theories are limited in expressing human relations as “owing” something to another.

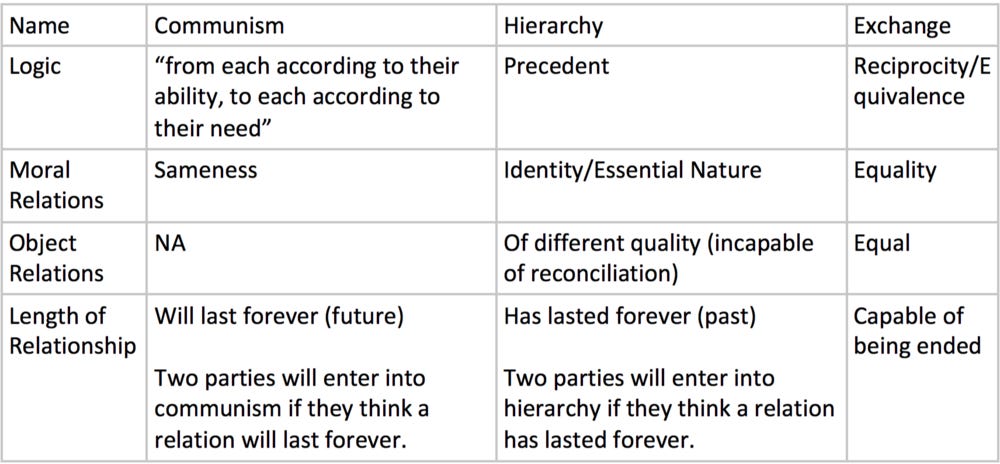

In Chapter 5, Graeber introduces three distinct types of social logic that he believes governs human relations. First, communism operates on the logic of “to each according to their need, from each according to their ability.” It describes the human impulse to help without expectation of return when the need is big enough or the ask is small enough. Second, exchange operates on the logic of equality. Both sides feel obliged to return to other what they received. This obligation is debt. Lastly, hierarchy operates on the logic of precedent: what is expected from a certain group currently is simply what has been expected from them before. With these threefold logic outlined, Graeber gives his definition of what debt is: an exchange that has not been brought to completion Debt is even more unbearable than hierarchy because it operates with the premises of exchange (equality) but within the reality of hierarchy (domination). He claims that the proliferation of the market and economics, has blinded us to both communism and hierarchy.

In Chapters 6 and 7, Graeber presents his historical construction of how we transitioned from gift economies (without money, neighbors giving aid to each other operating on both communism and exchange) to market economies. This inevitably takes us to a middle stage: human economies. Human economies are where money first came to be. These currencies (“social” currencies) were never used to buy or self anything, they were used to rearrange relations between people (Think, precious objects used to settle blood feuds or rearrange marriages). Importantly, they were never seen as equivalent to the people they were rearranging. This incommensurability was an expression of the uniqueness and preciousness of human lives. In Chapter 6, Graeber details how human economies become perverted when they are introduced to market economies: these exact same social currencies which used to express the value of human life, became the price to purchase humans for slavery. In Chapter 7, Graeber details how the slow transformation of human economies to market economies corrupts social mores. A key concept for him is going to be honor because of its dual meaning. Honor used to be an expression of the dignity of a person, but with the introduction of money, honor came to measure the power through which one can take away the dignity of another.

Here is one way to reconstruct Graeber’s economic history.

First, you have primitive, communist societies. These are hunter gatherer societies operating almost exclusively on the logic of communism and hierarchy. These people rarely operate on exchange unless it is with an outsider. There is nothing like a currency.

Next, you have gift economies. These are economies where the primary mode of economic behavior is giving gifts to one’s neighbors and expecting a roughly equivalent gift in one’s own time of future need. This tab, either physical or in one’s mind, is the closest thing to a currency. But, there is no one single denomination.

The next progression is human economies. The primary mode of economic behavior might still be the same as gift economies. But key social currencies develop. What defines human economies is that these social currencies (one denomination for many different social events) are expressions of the value of each human life. They are not taken to be equivalent to human life.

Then, you have, what we can call “heroic societies.” Medieval Ireland, with its honor price, may be a good example. Again, the primary mode of economic behavior may still be gift giving within one small community. The big difference is that, now, there is a clearly defined and set price to “buy” a single person. That is to say currency is seen as equivalent to human lives.

Lastly, you have market economies. This is where almost everything is seen as being tradeable with money. Of course, market economies vary greatly based on whether humans are tradeable (i.e. whether slavery is permitted). In the market economies which they are, human trading is even more perverse than in heroic societies: in heroic societies the currencies for an “honor price” aren’t equated with regular goods. That is to say there is no equivalence between a human and X number of shoes because the social currency is only used to exchange for humans. This is not true for market economies.

As you go down this progression (expanding the realm of things commensurable with money), Graeber wants to say that more violence is required. You need some degree of institutionalized violence to rearrange people in human economies and certainly to buy and sell slaves in heroic societies. He also wants to say that the concept of honor takes on a more perverse form. Whereas it signaled the dignity of a person in earlier societies, in the latter ones, honor is about your power to control others and protect people from being controlled. The idea is this: when humans become more tradeable and more easily uprooted from their social circumstance, it matters greatly whether one is the one doing the trading or being traded. Graeber sees this as the origin of patriarchy: it is only when the prostitution of debt-peons’ daughters and wives became pervasive did the most powerful men uphold chastity as a female virtue, preventing their women from engaging with public life. Another way to put this point is: as more things in the social world are denominated by money, more things and people become easily commensurable and comparable. As a result, people’s sense of worth is defined more relatively.

Clearly, a big difference within market economies is whether people are tradeable. Another important difference is whether the underlying currency is virtual/credit or real/bullion. In the former case, such as Mesopotamia, even though all the tabs are kept in silver, silver did not circulate outside specific institutions. Virtual market economies will take on many characteristics of gift economies (e.g. one’s reputation being extremely important in doing business). Chapters 8 – 12 are a reconstruction of economic history that interprets history as oscillating between periods of virtual and real currencies. I will not summarize all the insights in this briefing, but merely highlight one last definition that Graeber makes: capital. Graeber takes capital to be currency which has an imperative to grow. One way he shows this is how politics and war served the ends of money in the capitalist empires while money served the ends of politics and war in the Axial age. Another way he shows this is by pointing to the fact that the ban against usury was circumvented in the capitalist empires because interest was seen as compensation to the creditor for the other profitable ventures he could have but did not put his money in. In other words, money was expected to grow.

Part II: Reconstruction

Chapter 1

Graeber begins by giving a set of examples to show how deeply embedded yet complex (and confused) the concept of “debt” is.

Debt, in the global economy, can take upon many different forms. It can be what the weak owe the strong (e.g. Haiti, IMF). But, in the case of the US, it can also be owed from the strong to the weak. It is not the arrow of debt that determines who has the power but who controls the means of violence that shapes what these relationships look like and who ultimately benefits.

Debt is also infused into our moral and even religious language. Jesus’ salvation is described as “redemption.” We constantly are lectured on what we “owe” others and society. And our moral language operates under the logic of debt. Yet, in this moral framework there is a moral confusion about debt. We seem to both hold the position that 1. We should all pay back our debts 2. Anyone who lends money is evil. This ambivalence manifests in another way. It seems both morally bankrupt to be in debt but also to repay all of one’s debts:

On the one hand, insofar as all human relations involve debt, they are all morally compromised. Both parties are probably already guilty of something just by entering into the relation ship; at the very least they run a significant danger of becoming guilty if repayment is delayed. On the other hand, when we say someone acts like they "don't owe anything to anybody," we're hardly describing the person as a paragon of virtue.

Chapter 2: The Myth of Barter

Smith’s Founding Myth

Adam Smith was arguing against the Statist view of money: that money was created by the government. Presumably, because this would also give the government justification to intervene in matters of money ie. private property and the market.

Smith wanted to 1. Establish private property and the free market as an institution that shouldn’t be touched by the government (ie. Relegate the functioning of the government merely to preserving the functioning of markets) 2. Found the discipline of economics. He wanted to identify laws governing the market as systematic and deterministic as those of Newton's (of course, the only way to have these laws come to be is to assume that humans are rational calculating machines in it for their own interest). To justify the former, he goes to argue that markets and money really exist before the government. In fact, it is a natural evolution of primitive barter. To justify the latter, he needs to assume that in all matters of exchange, humans are merely looking to maximize their utility . In other words, economics (the sphere of exchange) had to be completely orthogonal to war, sex, honor, adventure, and any other human sphere. This was quite a novel thought in Smith's day as the idea that there existed the "economy" as a separate sphere was something new.

So Smith locates “a certain propensity in human nature . . . the propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another.” Graeber draws out the implications of Smith’s assumption: “Humans, if left to their own devices, will inevitably begin swapping and comparing things. This is just what humans do. Even logic and conversation are really just forms of trading, and as in all things, humans will always try to seek their own best advantage, to seek the greatest profit they can from the exchange.” Smith legitimizes this desire to barter for self-interest as a constitutive capacity of humanity and then goes on to paint a state of nature which begins with simple barter, evolves at the invention of money as a unit of account, store of value, and medium of exchange, and finally develops credit and other more advanced financial instruments. With this progression of history, Smith can relegate the role of government to merely protecting the system of exchange that existed before it.

Flipping the Story

The problem with this account of barter > money > credit is that there is no historical evidence for it. Barter only exists in two scenarios 1. When people who are used to the market (so people who exist after money was invented) live in an arrangement where money does not exist (think P.O.W. camp) 2. Before money was invented, you would only barter with strangers that you had no intention or expectation of coming across again. And this makes sense, you only want to maximize your own gain if you didn’t care about the other person:

What reason is there not to try to take advantage of such a person? If, on the other hand, one cares enough about someone-a neighbor, a friend-to wish to deal with her fairly and honestly, one will inevitably also care about her enough to take her individual needs, desires, and situation into account. Even if you do swap one thing for another, you are likely to frame the matter as a gift.

Instead what pre-money societies (what Graeber terms “gift economies”) usually operate on is more so credit than barter. You would go to your neighbor and simply ask for, say, a sandal with the expectation that you will give back something in the future in their time of need. There is also no unit of account here, as goods are separated into tiers. Where there is a social consensus that a chicken and a goose and a pair of sandals are roughly equivalent while an ox and a candle aren’t. Two important things to highlight here 1. These exchanges are usually framed in the language of gifts but there was a social expectation that there had to be an equivalence 2. This resolves the double coincidence of wants problem that money solves for Smith because you are eventually going to need something from your neighbor in the future. Ie. Everyone in a community expects to be with each other forever and so expect the balances to equal out eventually.

Even when money was invented, many times the coinage wasn’t available to the masses. So money became only the unit of account but not the medium of exchange nor store of value. People simply kept credit tabs denominated in currency:

In the marketplaces that cropped up in Mesopotamian cities, prices were also calculated in silver, and the prices of commodities that weren't entirely controlled by the Temples and Palaces would tend to fluctuate according to supply and demand. But even here, such evidence as we have suggests that most transactions were based on credit. Mer chants (who sometimes worked for the Temples, sometimes operated independently) were among the few people who did, often, actually use silver in transactions; but even they mostly did much of their dealings on credit, and ordinary people buying beer from "ale women," or local innkeepers, once again, did so by running up a tab, to be settled at harvest time in barley or anything they might have had at hand.

Graeber draws his surprising conclusion: Smith’s account of money is completely backwards. It did not go from barter > money > credit. Instead, credit was the natural arrangement (our fundamental capacity isn’t to truck and barter but to lend and repay), money was invented after (through warfare), and it is only in a society dominated by money do we start view everything under the logic of barter: reciprocation and exchange.

In fact, systematic exchange as we see today shouldn’t be recognized as a natural extension of what humans naturally do but as a violent turn away from nature. It’s not the absence of the state that allows the market to prosper but the existence of a very specific type of state:

It's money that had made it possible for us to imagine ourselves in the way economists encourage us to do: as a collection of individuals and nations whose main business is swapping things. It's also clear that the mere existence of money, in itself, is not enough to allow us see the world this way. If it were, the discipline of economics would have been created in ancient Sumer, or anyway, far earlier than 1776, when Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations appeared.

The missing element is in fact exactly the thing Smith was at tempting to downplay: the role of government policy. In England, in Smith's day, it became possible to see the market, the world of butchers, ironmongers, and haberdashers, as its own entirely independent sphere of human activity because the British government was actively engaged in fostering it. This required laws and police, but also, specific monetary policies, which liberals like Smith were (successfully) advocating. It required pegging the value of the currency to silver, but at the same time greatly increasing the money supply, and particularly the amount of small change in circulation. This not only required huge amounts of tin and copper, but also the careful regulation of the banks that were, at that time, the only source of paper money.

Chapter 3: Primordial Debts

The century before smith, attempts to create state-supported banks, based off of a completely different view of money failed spectacularly:

The century before The Wealth of Nations had seen at least two attempts to create state-supported central banks, in France and Sweden, that had proven to be spectacular failures. In each case, the would-be central bank issued notes based largely on speculation that collapsed the moment investors lost faith. Smith supported the use of paper money, but like Locke before him, he also believed that the relative success of the Bank of England and Bank of Scotland had been due to their policy of pegging paper money firmly to precious metals. This became the mainstream economic view, so much so that alternative theories of money as credit-the one that Mitchell-Innes advocated-were quickly relegated to the margins, their proponents written off as cranks, and the very sort of thinking that led to bad banks and speculative bubbles in the first place.

This chapter examines the alternative to Smith’s view: money as credit.

The credit theorists insists that money is not a commodity with an intrinsic value but it is an accounting tool, a unit of measurement:

You can no more touch a dollar or a deutschmark than you can touch an hour or a cubic centimeter. Units of currency are merely abstract units of measurement, and as the credit theorists correctly noted, historically, such abstract systems of accounting emerged long before the use of any particular token of exchange.

What does it measure? Debt: the promise of one person to pay another. You can see this is the case because gold coins usually circulate at face value and not the value of the underlying metal (which was usually less). Credit theorists insist that there is no real difference between credit such as a loan and money such as a gold coin. At the end of the day money is valuable because we always assume some person is going to accept it in exchange for a real good. Imagine if everyone in the world stopped accepting the USD, what we conceive of as “hard cash” will quickly take on the form of a defaulting credit relationship.

As primarily a mode of measurement, this theory has a more convincing story of how money came to be: the state. After all, the state is responsible for unifying the other modes of measurement. Of course unifying the measurement of debt under your currency gives you a degree of power that, say, unifying the measurement of height does not.

If we abide by the commodity theory of money, it becomes a puzzle why the state needs to collect taxes instead of, say, simply controlling the gold mines. Credit theorists explain this much more convincingly: by collecting taxes you are in effect dictating how people measure value, this often comes with enormous advantages for you since you can now create value out of thin air. Here is a hypothetical example:

Say a king wishes to support a standing army of fifty thousand men. Under ancient or medieval conditions, feeding such a force was an enormous problem-unless they were on the march, one would need to employ almost as many men and animals just to locate, acquire, and transport the necessary provisions. On the other hand, if one simply hands out coins to the soldiers and then demands that every family in the kingdom was obliged to pay one of those coins back to you, one would, in one blow, turn one's entire national economy into a vast machine for the provisioning of soldiers, since now every family, in order to get their hands on the coins, must find some way to contribute to the general effort to provide soldiers with things they want. Markets are brought into existence as a side effect.

Here is a historical example. Note that the primary role of tax collection here isn’t to collect value (he handed out the pieces of paper that he would eventually collect) but to create a cultural symbol and for formative reasons. This is even more powerful than the mere extraction of value as you are changing the rules by which the game is played:

This was particularly true in the colonial world. To return to Madagascar for a moment: I have already mentioned that one of the first things that the French general Gallieni, conqueror of Madagascar, did when the conquest of the island was complete in 1901 was to impose a head tax. Not only was this tax quite high, it was also only payable in newly issued Malagasy francs. In other words, Gallieni did indeed print money and then demand that everyone in the country give some of that money back to him.

Most striking of all, though, was language he used to describe this tax. It was referred to as the the "educational" or "moralizing tax." In other words, it was designed-to adopt the language of the day-to teach the natives the value of work. Since the "educational tax" came due shortly after harvest time, the easiest way for farmers to pay it was to sell a portion of their rice crop to the Chinese or Indian merchants who soon installed themselves in small towns across the country.

Money in today’s economy is, beyond a doubt, chartalist: created and stewarded by the state as a unit of measurement rather than a commodity with intrinsic value.

By the time of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the very notion that the market could regulate itself, so long as the government ensured that money was safely pegged to precious metals, was completely discredited. From roughly 1933 to 1979, every major capitalist government reversed course and adopted some version of Keynesianism. Keynesian orthodoxy started from the assumption that capitalist markets would not really work unless capitalist governments were willing effectively to play nanny: most famously, by engaging in massive deficit "pump-priming" during downturns.

To be sure this does not mean that the state is the ONLY creator of money but that it is the most natural entity to do so.

Primordial Debt Theory

This may answer why the state started to create taxes but it does not justify the act as legitimate. Here, Graeber turns to primordial debt theory that suggests we are born with infinite debt towards society and the state becomes the embodiment of that creditor:

The core argument is that any attempt to separate monetary policy from social policy is ultimately wrong. Primordial-debt theorists insist that these have always been the same thing. Governments use taxes to create money, and they are able to do so because they have become the guardians of the debt that all citizens have to one another. This debt is the essence of society itself. It exists long before money and markets, and money and markets themselves are simply ways of chopping pieces of it up.

The argument goes that this intrinsic sense of infinite indebtedness was first channeled through religion. In the earliest of Hindu texts, debt was synonymous with sin and guilt. In fact, our entire lives are plagued with guilt because we are forever indebted to the gods – a debt that we pay through ritual sacrifice.

The next move of the argument is to say that the state becomes the middleman between the gods and us in terms of repayment. We conceive the creditor of this debt as shifting from the gods to the entirety of society (not just the state but also, say, our fathers):

The first kings were sacred kings who were either gods in their own right or stood as privileged mediators between human beings and the ultimate forces that governed the cosmos. This sets us on a road to the gradual realization that our debt to the gods was always, really, a debt to the society that made us what we are.

In support of this genealogy, we can look at how often early currencies (cattle in Homeric Greece) were also what was offered in sacrifice to the gods. Ie. currency is that which was most fitting to giving to the gods.

But these debt theorists need to answer another important question: how did money become quantifiable? After all, I may wholeheartedly believe that I owe the state or someone I wronged cows, but still unsure how many cows I owe.

The next argumentative move of debt theorists is to say that currencies (that could be quantified) first developed not to acquire things but to rearrange relations, especially when settling disputes.

There is every reason to believe that our own money started the same way-even the English word "to pay" is originally derived from a word for "to pacify, appease"-as in, to give someone something precious, for instance, to express just how badly you feel about having just killed his brother in a drunken brawl, and how much you would really like to avoid this becoming the basis for an ongoing blood-feud.

The key insight here is that equivalence between qualitatively different goods (chicken vs. cows) is impossible to arrive at. The reason that we have arrived at ratios of equivalence must come from the specific instances where the human desire for equivalence is the strongest: when one feels wronged. In other words, the very ability for humans to think about any form of identity between objects and concepts lies in the strong urge to establish equivalence in moral relations between humans:

I've already remarked how difficult it is to imagine how a system of precise equivalences-one young healthy milk cow is equivalent to exactly thirty-six chickens-could arise from most forms of gift exchange. If Henry gives Joshua a pig and feels he has received an inadequate counter-gift, he might mock Joshua as a cheapskate, but he would have little occasion to come up with a mathematical formula for precisely how cheap he feels Joshua has been. On the other hand, if Joshua's pig just destroyed Henry's garden, and especially, if that led to a fight in which Henry lost a toe, and Henry's family is now hauling Joshua up in front of the village assembly-this is precisely the context where people are most likely to become petty and legalistic and express out rage if they feel they have received one groat less than was their rightful due. That means exact mathematical specificity: for instance, the capacity to measure the exact value of a two-year-old pregnant sow. What's more, the levying of penalties must have constantly required the calculation of equivalences. Say the fine is in marten pelts but the culprit's clan doesn't have any martens. How many squirrel skins will do? Or pieces of silver jewelry? Such problems must have come up all the time and led to at least a rough-and-ready set of rules of thumb over what sorts of valuable were equivalent to others. This would help explain why, for instance, medieval Welsh law codes can contain detailed breakdowns not only of the value of different ages and conditions of milk cow, but of the monetary value of every object likely to be found in an ordinary homestead, down to the cost of each piece of timber-despite the fact that there seems no reason to believe that most such items could even be purchased on the open market at the time.

The intuitions behind primordial debt theory (there is thing called society, we are indebted to it, governments are secular gods and natural representatives of it) came out of the French revolution: during the birth of the modern state. If the commodity theory of money has led to the liberal capitalist empires of the 20th century, then the credit theory of money has led to the socialist ones. The USSR, for example, often employed Vedic logic to justify preventing emigration:

The argument was always: The USSR created these people, the USSR raised and educated them, made them who they are. What right do they have to take the product of our investment and transfer it to another country, as if they didn't owe us anything? Neither is this rhetoric restricted to socialist regimes. Nationalists appeal to exactly the same kind of arguments--especially in times of war. And all mod ern governments are nationalist to some degree.

One might even say that what we really have, in the idea of primordial debt, is the ultimate nationalist myth. Once we owed our lives to the gods that created us, paid interest in the form of animal sacrifice, and ultimately paid back the principal with our lives. Now we owe it to the Nation that formed us, pay interest in the form of taxes, and when it comes time to defend the nation against its enemies, to offer to pay it with our lives.

In summary, the Primordial Debt theorists’ justification for taxation is that it is a constant in human nature to think of us as infinitely indebted to the world. We can see this urge of human nature in our earliest relationship with gods. The state is the natural entity to steward this debt.

The Problem with Primordial-Debt Theory

Graeber’s problem with Primordial-Debt theory is that it starts off on the wrong premise: that we begin with infinite indebtedness to the world. This poses a few challenges. First, who are we exactly indebted to? Is it all of humanity or a specific subgroup. Second, how do we pay a debt so diffuse and unspecified. Third, who possibly has the authority to act as the creditor: to tell us how to repay our debts.

These paradoxes become apparent when we look at how Vedic interpreters conceive of how we ought to repay such a debt:

• To the universe, cosmic forces, as we would put it now, to Nature. The ground of our existence. To be repaid through ritual: ritual being an act of respect and recognition to all that beside which we are small.

• To those who have created the knowledge and cultural accomplishments that we value most; that give our existence its form, its meaning, but also its shape. Here we would include not only the philosophers and scientists who created our intellectual tradition but everyone from William Shakespeare to that long-since-forgotten woman, somewhere in the Middle East, who created leavened bread. We repay them by becoming learned ourselves and contributing to human knowledge and human culture.

• To our parents, and their parents-our ancestors. We repay them by becoming ancestors.

• To humanity as a whole. We repay them by generosity to strangers, by maintaining that basic communistic ground of sociality that makes human relations, and hence life, possible.

What’s odd is that this logic functions nothing like a commercial debt. The way to repay here is to merge with your creditor. Perhaps the real crime is thinking that we are separate and equal enough to enter into debt relationships with these entities. Ie. Thinking that we are in debt or guilty to these entities, implies our belief in our separation from and equality with them, that is what we are really guilty of:

Or even that the very presumption of positing oneself as separate from humanity or the cosmos, so much so that one can enter into one-to-one dealings with it, is itself the crime that can be answered only by death. Our guilt is not due to the fact that we cannot repay our debt to the universe. Our guilt is our presumption in thinking of ourselves as being in any sense an equivalent to Everything Else that Exists or Has Ever Existed, so as to be able to conceive of such a debt in the first place

Perhaps what the Vedic commentators were trying to show by framing our relationship with the cosmos in the language of debt is that it cannot be fundamentally framed in the language of debt.

In fact, we can find the same tension in Christianity as well. It may be odd to think about the coming of Christ in the language of a financial transaction: "Redeemer." But if we dig closer we will see that to redeem is not referring to paying one's debts but to the removal of all debts: the destruction of the accounting system. In similar manner, financial language is used to show the inadequacy of financial language:

Nehemiah was a Jew born in Babylon, a former cup-bearer to the Persian emperor. In 444 Be, he managed to talk the Great King into appointing him governor of his native Judaea. He also received per mission to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem that had been destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar more than two centuries earlier. In the course of rebuilding, sacred texts were recovered and restored; in a sense, this was the moment of the creation of what we now consider Judaism.

The problem was that Nehemiah quickly found himself confronted with a social crisis. All around him, impoverished peasants were un able to pay their taxes; creditors were carrying off the children of the poor. His first response was to issue a classic Babylonian-style "clean slate" edict-having himself been born in Babylon, he was clearly familiar with the general principle. All non-commercial debts were to be forgiven. Maximum interest rates were set. At the same time, though, Nehemiah managed to locate, revise, and reissue much older Jewish laws, now preserved in Exodus, Deuteronomy, and Leviticus, which in certain ways went even further, by institutionalizing the principle. The most famous of these is the Law of Jubilee: a law that stipulated that all debts would be automatically cancelled "in the Sabbath year" (that is, after seven years had passed), and that all who languished in bondage owing to such debts would be released.

"Freedom," in the Bible, as in Mesopotamia, came to refer above all to release from the effects of debt. Over time, the history of the Jewish people itself came to be interpreted in this light: the liberation from bondage in Egypt was God's first, paradigmatic act of redemption; the historical tribulations of the Jews (defeat, conquest, exile) were seen as misfortunes that would eventually lead to a final redemption with the coming of the Messiah-though this could only be accomplished, prophets such as Jeremiah warned them, after the Jewish people truly repented of their sins (carrying each other off into bondage, whoring after false gods, the violation of commandments)Y In this light, the adoption of the term by Christians is hardly surprising. Redemption was a release from one's burden of sin and guilt, and the end of history would be that moment when all slates are wiped clean and all debts finally lifted when a great blast from angelic trumpets will announce the final Jubilee.

If so, "redemption" is no longer about buying something back. It's really more a matter of destroying the entire system of accounting. In many Middle Eastern cities, this was literally true: one of the common acts during debt cancelation was the ceremonial destruction of the tablets on which financial records had been kept, an act to be repeated, much less officially, in just about every major peasant revolt in history.

Furthermore in the Lord's prayer, we say "forgive us of our debts as we forgive those of our debtors." The problem is we don't forgive our debtors at all. The implicit message here could be, again, that the forgiveness by God (first half of the sentence) can't possibly be framed in the language of financial transactions:

What's more, there is the lingering suggestion that we really couldn't live up to those standards, even if we tried. One of the things that makes the Jesus of the New Testament such a tantalizing character is that it's never clear what he's telling us. Everything can be read two ways. When he calls on his followers to forgive all debts, refuse to cast the first stone, turn the other cheek, love their enemies, to hand over their possessions to the poor-is he really expecting them to do this? Or are such demands just a way of throwing in their faces that, since we are clearly not prepared to act this way, we are all sinners whose salvation can only come in another world-a position that can be (and has been) used to justify almost anything? This is a vision of human life as inherently corrupt, but it also frames even spiritual affairs in com mercial terms: with calculations of sin, penance, and absolution, the Devil and St. Peter with their rival ledger books, usually accompanied by the creeping feeling that it's all a charade because the very fact that we are reduced to playing such a game of tabulating sins reveals us to be fundamentally unworthy of forgiveness.

Graeber's claim is that all of these religions arose in the Axial age when markets and coinage first started to dominate and enter into the way that we have conceived of things. That is why these traditions framed relationships with god and morality in general as financial transactions. But they all go to show by this very framing how morality cannot be conceived of in these terms.

Chapter 4: Cruelty and Redemption

What is Money

Graeber affirms both theories’ (primordial debt and barter) understanding of what money is. Money is both a commodity and an IOU. It can’t be just the former because people never needed it to make barter easier. But it also can’t just be the latter because trust is hard to come by. In other words, if your IOU also has intrinsic value (as a commodity) it would make for better money because it would be harder to fabricate. This is why a gold coin with an emperor’s face stamped on it often went for higher than the value of the metal (added trust that the emperor would accept it).

Historically, money would alter between IOU and commodity. In periods of low trust (war) money had to be more of a commodity (gold). In periods of high trust (stability) money was more likely to be IOU (USD). In fact, learning what is accepted as currency often tells you a great deal of the political landscape:

One could often learn a lot about the balance of political forces in a given time and place by what sorts of things were accept able as currency. For instance: in much the same way that colonial Virginia planters managed to pass a law obliging shopkeepers to accept their tobacco as currency, medieval Pomeranian peasants appear to have at certain points convinced their rulers to make taxes, fees, and customs duties, which were registered in Roman currency, actually payable in wine, cheese, peppers, chickens, eggs, and even herring much to the annoyance of traveling merchants, who therefore had to either carry such things around in order to pay the tolls or buy them locally at prices that would have been more advantageous to their suppliers for that very reason. This was in an area with a free peasantry, rather than serfs. They were in a relatively strong political position. In other times and places, the interests of lords and merchants prevailed instead.

What isn’t Morality

Paradoxically, after accepting both theories’ view of money, he goes on to reject both of their views of morality: that we are either not indebted to anyone at all or fully indebted to the cosmos. He paints this as a false dichotomy that supposedly contains between them the realm of possibility. Where they both start off with (and get wrong on) is to think that commercial relations (debt and exchange) encompasses the whole of moral relations.

Graeber draws upon Nietzsche to show how, if we start off with Smith’s premise of humans as creatures of exchange, capable of creating debts freely, we will naturally conceive of our relationship with the cosmos in debt as well.

Nietzsche's second essay in the genealogy details how the logic of debt transitioned to the logic of guilt. The starting state is when punishment is conceived of as a repayment of debt. Specifically, the creditor rejoices in the pain inflicted upon the debtor. This is considered cheerful because the debts are sought to be squared after this act of punishment and both can go about on their own ways. Guilt certainly existed, but only before the act of punishment. The guilt was clearly identifiable and small enough that you would be rid of your guilt once you submit yourself to the equivalent level of punishment. This was the basis of social structures and relationships:

The feeling of guilt, of personal obligation, has its origin in the oldest and most primitive personal relationship there is, in the relationship between seller and buyer, creditor and debtor. Here for the first time one person moved up against another person, here an individual measured himself against another individual. We have found no civilization still at such a low level that something of this relationship is not already perceptible. To set prices, to measure values, to think up equivalencies, to exchange things-that preoccupied man's very first thinking to such a degree that in a certain sense it's what thinking itself is. Here the oldest form of astuteness was bred; here, too, we can assume are the first beginnings of man's pride, his feeling of pre-eminence in relation to other animals. Perhaps our word "man" (manas) continues to ex press directly something of this feeling of the self: the human being describes himself as a being which assesses values, which values and measures, as the "inherently calculating animal." Selling and buying, together with their psychological attributes, are even older than the beginnings of any form of social organizations and groupings; out of the most rudimentary form of personal legal rights the budding feeling of exchange, contract, guilt, law, duty, and compensation was instead first transferred to the crudest and earliest social structures (in their relation ships with similar social structures), along with the habit of comparing power with power, of measuring, of calculating.

(Again, we see here the thesis that our intellectual capabilities for calculation and comparison come from our urge for moral comparison)

The transition has five interlinked movements: 1. the ascription of free will to the debtor: the debtor is now being punished because he could've done otherwise 2. the expansion of the creditor: when we enter into society this logic of debt becomes natural way we conceive of our relationship with the community. The creditor expands even more when we conceive of our relationship with the cosmos or God in this way. 3. As the creditor expands so does the debt. It both increases as well as becomes amorphous to the point where there is no possibility of you paying it off. The debt becomes constant. 4. the internalization of the will to power: prior, the will to power was directed externally when experiencing joy when watching the pain of your creditor. Now, the will to power is directed within yourself, your "free will", and feeling bad about your own inclinations. 5. the shift of focus from the creditor to the debtor: the act of punishment is now not to reward the creditor but because the debtor deserves this.

With these five moments we've started from debt and arrived at an ell encompassing guilt, a bad consciousness.

Graeber emphasizes the second of these movements to show how Nietzsche's genealogical story reveals that the myth of barter and the myth of primordial-debt really start from the same premises. Specifically, if you view human relations exclusively in terms of exchange, as the former does, you will naturally conceive of your relationship with society, the cosmos, and God in such a manner, as the latter does:

When humans did begin to form communities, Nietzsche continues, they necessarily began to imagine their relationship to the com munity in these terms. The tribe provides them with peace and security. They are therefore in its debt. Obeying its laws is a way of paying it back ("paying your debt to society" again). But this debt, he says, is also paid-here too-in sacrifice:

Within the original tribal cooperatives-we're talking about primeval times-the living generation always acknowledged a legal obligation to the previous generations, and especially to the earliest one which had founded the tribe [ . . . ] Here the reigning conviction is that the tribe only exists at all only be cause of the sacrifices and achievements of its ancestors-and that people have to pay them back with sacrifices and achieve ments. In this people recognize a debt which keeps steadily growing because these ancestors in their continuing existence as powerful spirits do not stop giving the tribe new advantages and lending them their power. Do they do this for free? But there is no "for free" for those raw and "spiritually destitute" ages. What can people give back to them? Sacrifices (at first as nourishment understood very crudely), festivals, chapels, signs of honor, above all, obedience--for all customs, as work of one's ancestors, are also their statutes and commands. Do people ever give them enough? This suspicion remains and grows.

In other words, for Nietzsche, starting from Adam Smith's assumptions about human nature means we must necessarily end up with something very much along the lines of primordial-debt theory. On the one hand, it is because of our feeling of debt to the ancestors that we obey the ancestral laws: this is why we feel that the community has the right to react "like an angry creditor" and punish us for our transgressions if we break them. In a larger sense, we develop a creeping feeling that we could never really pay back the ancestors, that no sacrifice (not even the sacrifice of our first-born) will ever truly redeem us. We are terrified of the ancestors, and the stronger and more powerful a com munity becomes, the more powerful they seem to be, until finally, "the ancestor is necessarily transfigured into a god." As communities grow into kingdoms and kingdoms into universal empires, the gods them selves come to seem more universal, they take on grander, more cosmic pretentions, ruling the heavens, casting thunderbolts-culminating in the Christian god, who, as the maximal deity, necessarily "brought about the maximum feeling of indebtedness on earth." Even our ancestor Adam is no longer figured as a creditor, but as a transgressor, and therefore a debtor, who passes on to us his burden of Original Sin:

Finally, with the impossibility of discharging the debt, people also come up with the notion that it is impossible to remove the penance, the idea that it cannot be paid off ("eternal punishment") . . . until all of a sudden we confront the paradoxical and horrifying expedient with which a martyred humanity found temporary relief, that stroke of genius of Christianity: God sacrificing himself for the guilt of human beings, God paying himself back with himself, God as the only one who can re deem man from what for human beings has become impossible to redeem-the creditor sacrificing himself for the debtor, out of love (can people believe that?), out of love for his debtor!

It is this false assumption: that all morality can be framed in the language of commercial transactions that is problematic. In fact, rather than seeing the ability to calculate and keep tabs as that which is quintessentially human, egalitarian societies often saw it as not doing so as what makes us human. Graeber will later argue that to be able to reduce morality to debt, to impersonal numbers requires us to violently strip out all our moral relationships to things and other people:

Freuchen tells how one day, after coming home hungry from an unsuccessful walrus-hunting expedition, he found one of the successful hunters dropping off several hundred pounds of meat. He thanked him profusely. The man objected indignantly: "Up in our country we are human!" said the hunter. "And since we are human we help each other. We don't like to hear anybody say thanks for that. What I get today you may get tomorrow. Up here we say that by gifts one makes slaves and by whips one makes dogs."

The last line is something of an anthropological classic, and similar statements about the refusal to calculate credits and debits can be found through the anthropological literature on egalitarian hunting societies. Rather than seeing himself as human because he could make economic calculations, the hunter insisted that being truly human meant refusing to make such calculations, refusing to measure or remember who had given what to whom, for the precise reason that doing so would inevitably create a world where we began "comparing power with power, measuring, calculating" and reducing each other to slaves or dogs through debt.

Chapter 5: A Brief Treatise on the Moral Grounds of Economic Relations

If, as the religious traditions show morality cannot be conceived of in the logic of debt, how can morality be conceived? Graeber suggests three types of moral logic: communism, exchange, and hierarchy. Debt is merely the obligation generated within exchange. Communism and hierarchy will have their own obligations.

Communism

Communism is governed by the principle of “from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.” The obligation is to help others when they need it and to contribute according to one’s abilities. Any small team or social unit operates in this way.

If the “from each” element is small enough (asking for directions) or the “to each” element is big enough relative to the “from each” (someone is drowning) we expect people who are not explicitly enemies to operate under this logic.

But of course, the extent to which someone follows this logic is determined by the society. Often, if this is the dominant logic of a community, there is a presumption of eternity, that you are always going to be interacting with them. And there is some shared identity (e.g. tribesman, or humanity).

“The surest way to know that one is in the presence of communistic relations is that not only are no accounts taken, but it would be considered offensive, or simply bizarre, to even consider doing so.” For example if siblings always kept tallies of who helped who.

We almost operate on this logic to some degree even in commerce: e.g. merchants reducing prices for the needy.

Exchange

The logic of exchange is equivalence. Both sides feel obliged to return to other what they received. This obligation is debt. Framed in this abstract way it is clear that exchange is not always about sharing value (commerce) but can also be an exchange of blows or warfare. Different from communism, actors within exchange keep clear accounts.

Instead of a common shared identity, as in the case with communism, parties in exchange are defined by equality. This is also why I wouldn’t feel the need to reciprocate if Bill Gates treated me out to dinner but would if my friend did:

In exchange, the objects being traded are seen as equivalent. Therefore, by implication, so are the people: at least, at the moment when gift is met with counter-gift, or money changes hands; when there is no further debt or obligation and each of the two parties is equally free to walk away. This in turn implies autonomy.

Certainly, sometimes, what each side is aiming for is not equivalence but to outdo the other. But the logic is similar: to return what one received with interest – it is still equivalence in a looser term. (This is why exchange can transform into hierarchy) So the relationship as a whole tends towards equilibrium even if both parties aim to break equilibrium.

Furthermore, there is no presumption of eternity and there is always a possibility that the relationship could end. Thus, communities based on exchange needs to always be maintained and repayments of exactly the same amount seem offensive because they represent an urge to square accounts and stop all future dealings:

Exchange allows us to cancel out our debts. It gives us a way to call it even: hence, to end the relationship. With vendors, one is usu ally only pretending to have a relationship at all. With neighbors, one might for this very reason prefer not to pay one's debts. Laura Bohannan writes about arriving in a Tiv community in rural Nigeria; neighbors immediately began arriving bearing little gifts: "two ears corn, one vegetable marrow, one chicken, five tomatoes, one handful peanuts." Having no idea what was expected of her, she thanked them and wrote down in a notebook their names and what they had brought. Eventually, two women adopted her and explained that all such gifts did have to be returned. It would be entirely inappropriate to simply accept three eggs from a neighbor and never bring anything back. One did not have to bring back eggs, but one should bring some thing back of approximately the same value. One could even bring money-there was nothing inappropriate in that-provided one did so at a discreet interval, and above all, that one did not bring the exact cost of the eggs. It had to be either a bit more or a bit less. To bring back nothing at all would be to cast oneself as an exploiter or a parasite. To bring back an exact equivalent would be to suggest that one no longer wishes to have anything to do with the neighbor. Tiv women, she learned, might spend a good part of the day walking for miles to distant homesteads to return a handful of okra or a tiny bit of change, "in an endless circle of gifts to which no one ever handed over the precise value of the object last received"-and in doing so, they were continually creating their society. There was certainly a trace of communism here--neighbors on good terms could also be trusted to help each other out in emergencies-but unlike communistic relations, which are assumed to be permanent, this sort of neighborliness had to be constantly created and maintained, because any link can be broken off at any time.

Finally, relationships of pure exchange are hard to identify because we have an urge to pretend we are more than just calculating machines wanting nothing to do with each other after the transaction. So even parties haggling in a night market might feel pressured to put on a more personable façade.

Hierarchy

Hierarchy operates on the logic of precedent: what is expected from a certain group currently is simply what has been expected from them before. In fact, it is dangerous to give gifts to people higher up or lower than you for this precise reason: that it will be considered precedent.

And this makes sense: in communism, ability and need specify what was done. In exchange, equivalence demanded what was to be exchanged. There is no inherent logic of hierarchy (it is saying that the parties are inherently different and incommensurable) as there is in the other two, so the logic is simply based on precedent.

In relations of hierarchy, there develops identities or essential natures. Someone does something because it is in their nature to do so. That is why hierarchy may be a misleading name here, it’s not so much an objective ranking of different natures but a recognition of different natures (that may not be able to be ordinally ranked) which separates it from communism and exchange:

Often, such arrangements can turn into a logic of caste: certain clans are responsible for weaving the ceremonial garments, or bringing the fish for royal feasts, or cutting the king's hair. They thus come to be known as weavers or fishermen or barbers. This last point can't be overemphasized because it brings home another truth regularly over looked: that the logic of identity is, always and everywhere, entangled in the logic of hierarchy. It is only when certain people are placed above others, or where everyone is being ranked in relation to the king, or the high priest, or Founding Fathers, that one begins to speak of people bound by their essential nature: about fundamentally different kinds of human being. Ideologies of caste or race are just extreme examples. It happens whenever one group is seen as raising themselves above others, or placing themselves below others, in such a way that ordinary standards of fair dealing no longer apply.

In fact, something like this happens in a small way even in our most intimate social relations. The moment we recognize someone as a different sort of person, either above or below us, then ordinary rules of reciprocity become modified or are set aside. If a friend is unusually generous once, we will likely wish to reciprocate. If she acts this way repeatedly, we conclude she is a generous person, and are hence less likely to reciprocate.

We can describe a simple formula here: a certain action, repeated, becomes customary; as a result, it comes to define the actor's essential nature.

In like manner, not only is there a qualitative difference between people but there is also a qualitative difference between the goods exchanged.

Hierarchy, however, can be merely a channel of redistribution:

In much of Papua New Guinea, social life centers on "big men," charismatic individuals who spend much of their time coaxing, cajoling, and manipulating in order to acquire masses of wealth to give away again at some great feast. One could, in practice, pass from here to, say, an Amazonian or indigenous North American chief. Unlike big men, their role is more formalized; but actually such chiefs have no power to compel anyone to do anything they don't want to (hence North American Indian chiefs' famous skill at oratory and powers of persuasion). As a result, they tended to give away far more than they received. Observers often remarked that in terms of personal possessions, a village chief was often the poorest man in the village, such was the pressure on him for constant supply of largesse.

There tends to be a correlation between how much wealth is gathered on the top and how violently it is gathered with how spectacular my act of giving it away must be and how much I have to foster identities within a group. The idea must be this: if I gathered a lot of wealth through wealth and plunder, the only way I could justify this is if I tell a story about how some people (e.g. the rich) are essentially bad in nature. I must also, the idea goes, make a big show of giving it away to alleviate the tensions I created from my plundering. The redistributive state has its origins more in hierarchy then communism:

And what is true of warrior aristocracies is all the more true of ancient states, where rulers almost invariably represented themselves as the protectors of the helpless, supporters of widows and orphans, and champions of the poor. The genealogy of the modern redistributive state-with its notorious tendency to foster identity politics-can be traced back not to any sort of "primitive communism" but ultimately to violence and war.

Stage Transitions

Graeber concedes that 1. Every relationship is probably a mixture of these three 2. These three relations can easily descend into the other. (Although some transitions from communism to exchange, for example, are much more difficult) The reason we think that everything is exchange however is because 1. How much the market has penetrated into our everyday thinking (historically contingent) 2. As humans, we have a natural tendency to envision justice as symmetry and therefore reciprocity.

We are at a point where we can meaningfully answer what “Debt” is: “an exchange that has not been brought to completion.” Debt has to happen between two separate equals. It can neither be between relations of communism (where no one is keeping tallies) nor hierarchies (where things are expected from certain people). Furthermore, there must still be, at least the logical possibility, of them returning to equality:

This is what makes situations of effectively unpayable debt so difficult and so painful. Since creditor and debtor are ultimately equals, if the debtor cannot do what it takes to restore herself to equality, there is obviously something wrong with her; it must be her fault.

This connection becomes clear if we look at the etymology of common words for "debt" in European languages. Many are synonyms for "fault," "sin," or "guilt;" just as a criminal owes a debt to society, a debtor is always a sort of criminal.

What is so peculiar about debt is that it only exists when the exchange has not completed, when only one party has transacted. Therefore, debt, despite grounded in the morality of equal exchange, also somewhat operates on the logic of hierarchy. The relationship with you and your debtor is an uncomfortable mix between hierarchy and equality:

Debtor and creditor confront each other like a peasant before a feudal lord. The law of precedent takes hold. If you bring your creditor tomatoes from the garden, it never occurs to you that he would give something back. He might expect you to do it again, though.

This is neither a good nor bad thing in itself. On the positive side, debt puts people who otherwise would have nothing to do with each other (this is what equality implies: seperation) into moral relationships:

Debt is what happens in between: when the two parties cannot yet walk away from each other, because they are not yet equal. But it is carried out in the shadow of eventual equality. Because achieving that equality, however, destroys the very reason for having a relation ship, just about everything interesting happens in between. In fact, just about everything human happens in between-even if this means that all such human relations bear with them at least a tiny element of criminality, guilt, or shame.

For the Tiv women whom I mentioned earlier in the chapter, this wasn't much of a problem. By ensuring that everyone was always slightly in debt to one another, they actually created human society, if a very fragile sort of society-a delicate web made up of obligations to return three eggs or a bag of okra, ties renewed and recreated, as any one of them could be cancelled out at any time.

A Culture of “Please” and “Thank You”

Our insistence on saying “please” and “thank you” reveals the commercial nature of our culture. These words imply that you are dealing with equal and separate individuals that could have done otherwise. In hierarchy, a lord will never thank a barber for fulfilling his function: that is what he IS. Similarly, in communism, it would be extremely weird for a child to thank her mother for every act of help because it would imply that the child expected the mother to not be so caring. What this tells us is, first and foremost, that we think we live in a community of separate, equal, and essence-less individuals. “It is also merely one token of a much larger philosophy, a set of assumptions of what humans are and what they owe one another, that have by now become so deeply ingrained that we cannot see them.”

But it is even more interesting when we look at the etymologies for these phrases.

Saying please means, literally and etymologically, that you have no obligation to do something. But, of course, there is an obligation:

In fact, the English "please" is short for "if you please," "if it pleases you to do this"-it is the same in most European languages (French si il vous plait, Spanish por favor). Its literal meaning is "you are under no obligation to do this." "Hand me the salt. Not that I am saying that you have to!" This is not true; there is a social obligation, and it would be almost impossible not to comply. But etiquette largely consists of the exchange of polite fictions (to use less polite language, lies). When you ask someone to pass the salt, you are also giving them an order; by attaching the word "please," you are saying that it is not an order. But, in fact, it is.

In like manner, the literal meaning of “thank you” is that I will record done what you did for me (breaking equal relationship and entering into debt). But the implied meaning of it is that we didn’t have any relationship to begin with and you could of not done that.

In English, "thank you" derives from "think," it originally meant, "I will remember what you did for me''-which is usually not true either-but in other languages (the Portuguese obrigado is a good example) the standard term follows the form of the English "much obliged"-it actually does means "I am in your debt." The French merci is even more graphic: it derives from "mercy," as in begging for mercy; by saying it you are symbolically placing yourself in your bene factor's power-since a debtor is, after all, a criminal. Saying "you're welcome," or "it's nothing" (French de rien, Spanish de nada)-the latter has at least the advantage of often being literally true-is a way of reassuring the one to whom one has passed the salt that you are not actually inscribing a debit in your imaginary moral account book. So is saying "my pleasure"-you are saying, "No, actually, it's a credit, not a debit-you did me a favor because in asking me to pass the salt, you gave me the opportunity to do something I found rewarding in itself!"

What this reveals is two things. First, how we are really ignoring relationships that are actually hierarchical and communistic: that is why there is a dual and conflicting meaning of these phrases.

Second, it shows the fragility of equality in our culture. Much like the schizophrenic logic of debt which sits uncomfortably between equality and hierarchy so too does our everyday relationships. The literal meaning of “please” is that we are free individuals with no obligations, yet the social meaning is that you are obliged to help me. The literal meaning of “thank you” is that I am in your debt and have obligations towards you, whereas the implication of even saying it in the first place is that we had no obligations towards each other.

Chapter 6: Games with Sex and Death

If we just view economic history in the logic of equal exchange then we will be overlooking much of human activity. Even exchange itself, at the extremes, takes upon logic of communism or hierarchy.

Graeber begins telling his version of economic history that goes from credit > money > barter. Early communities begin with people operating on gifts. They kept accounting by agreeing upon a rough equivalence between goods, money didn’t necessarily have to form. Money begins forming in “human economies” and takes upon their modern form in “market economies” which tend to oscillate between virtual and real forms of money. And it is only in this last evolution to “market economies” do we establish our propensity to barter: to quantify and equate.

To understand the modern intuitions of money and debt we, therefore, have to understand the transition from human economies to market economies. In this chapter, we examine what happens when human economies are exposed to market economies. In the next, we see how the transition naturally happens.

Money in Human Economies

Graeber’s definition of human economies:

Currencies are never used to buy and sell anything at all. Instead, they are used to create, maintain, and otherwise reorganize relations between people: to arrange marriages, establish the paternity of children, head off feuds, console mourners at funerals, seek forgiveness in the case of crimes, negotiate treaties, acquire followers almost anything but trade in yams, shovels, pigs, or jewelry.

Often, these currencies were extremely important, so much so that social life itself might be said to revolve around getting and disposing of the stuff. Clearly, though, they mark a totally different conception of what money, or indeed an economy, is actually about. I've decided therefore to refer to them as "social currencies," and the economies that employ them as "human economies." By this I mean not that these societies are necessarily in any way more humane (some are quite humane; others extraordinarily brutal), but only that they are economic systems primarily concerned not with the accumulation of wealth, but with the creation, destruction, and rearranging of human beings.

The role of money in human economies is not to buy things, it is not to establish equivalence. It is a recognition that an equivalence can never be made. Take “bride price” for example. It may look like you are buying a wife, but that would be inaccurate because 1. You can’t sell the wife 2. You have moral obligations to her 3. There is no equivalent amount of goods you can give for her, you continuously need to pay, and no one would think that your debt to the family has been repaid. In this example, the prestigious brass rods are a symbol that you know there is a debt that can never be repaid, that money and a person are qualitatively different things incapable of equivalence:

The Tiv at that time used bundles of brass rods as their most prestigious form of currency. Brass rods were only held by men, and never used to buy things in markets (markets were dominated by women); instead, they were exchanged only for things that men considered of higher importance: cattle, horses, ivory, ritual titles, medical treatment, magical charms. It was possible, as one Tiv ethnographer, Akiga Sai, explains, to acquire a wife with brass rods, but it required quite a lot of them. You would need to give two or three bundles of them to her parents to establish yourself as a suitor; then, when you did finally make off with her (such marriages were always first framed as elopements), another few bundles to assuage her mother when she showed up angrily demanding to know what was going on. This would normally be followed by five more to get her guardian to at least temporarily accept the situation, and more still to her parents when she gave birth, if you were to have any chance of their accepting your claims to be the father of her children. That might get her parents off your back, but you'd have to pay off the guardian forever, because you could never really use money to acquire the rights to a woman. Everyone knew that the only thing you can legitimately give in exchange for a woman is another woman. In this case, everyone has to abide by the pretext that a woman will someday be forthcoming. In the meantime, as one ethnographer succinctly puts it, "the debt can never be fully paid."

The same holds true for blood feuds. You might have to pay the family whom you injured, but there is never a sense that the accounts have been settled. The only thing that is equivalent to a human life is another human life. So you would develop economies where the males all wanted to hoard females that could be exchanged with each other:

Among North African Bedouins, for instance, it sometimes happened that the only way to settle a feud was for the killer's family to turn over a daughter, who would then marry the victim's next of kin-his brother, say.

This is very much like primordial debt theory: money is a recognition that there is an absolute debt that cannot be repaid. This is also why, money in human societies were often extremely social objects:

Lele currencies are, as I say, quintessential social currencies. They are used to mark every visit, every promise, every important moment in a man's or woman's life. It is surely significant, too, what the objects used as currency here actually were. Raffia cloth was used for clothing. In Douglas's day, it was the main thing used to clothe the human body; camwood bars were the source of a red paste that was used as a cosmetic-it was the main substance used as makeup, by both men and women, to beautify themselves each day. These, then, were the materials used to shape people's physical appearance, to make them appear mature, decent, attractive, and dignified to their fellows. They were what turned a mere naked body into a proper social being.

This is no coincidence. In fact, it's extraordinarily common in what I've been calling human economies. Money almost always arises first from objects that are used primarily as adornment of the person. Beads, shells, feathers, dog or whale teeth, gold, and silver are all well known cases in point. All are useless for any purpose other than making people look more interesting, and hence, more beautiful. The brass rods used by the Tiv might seem an exception, but actually they're not: they were used mainly as raw material for the manufacture of jewelry, or simply twisted into hoops and worn at dances. There are exceptions (cattle, for instance), but as a general rule, it's only when governments, and then markets, enter the picture that we begin to see currencies like barley, cheese, tobacco, or salt.

Three Tiers of Violence

Money begins as a recognition that humans are unique qualities incapable of being exchanged for quantities. Graeber goes on to paint a picture of how violence makes humans fundamentally calculable and tradeable:

How is this calculability effectuated? How does it become possible to treat people as if they are identical? The Lele example gave us a hint: to make a human being an object of exchange, one woman equivalent to another for example, requires first of all ripping her from her context; that is, tearing her away from that web of relations that makes her the unique conflux of relations that she is, and thus, into a generic value capable of being added and subtracted and used as a means to measure debt. This requires a certain violence. To make her equivalent to a bar of camwood takes even more violence, and it takes an enormous amount of sustained and systematic violence to rip her so completely from her context that she becomes a slave.

The first level of violence comes from Lele logic itself. The equivalence of human life for human life is, in itself, an equivalence that collapses qualities into quantities. And this equivalence was only possible through the threat of violence:

Human beings, left to follow their own desires, rarely arrange themselves in symmetrical patterns [(patterns that meant equivalence could be established)]. Such symmetry tends to be bought at a terrible human price. In the Tiv case, Akiga is actually willing to describe it:

Under the old system an elder who had a ward could always marry a young girl, however senile he might be, even if he were a leper with no hands or feet; no girl would dare to refuse him. If another man were attracted by his ward he would take his own and give her to the old man by force, in order to make an exchange. The girl had to go with the old man, sorrowfully carrying his goat-skin bag. If she ran back to her home her owner caught her and beat her, then bound her and brought her back to the elder. The old man was pleased, and grinned till he showed his blackened molars. "Wherever you go," he told her, "you will be brought back here to me; so stop worrying, and settle down as my wife." The girl fretted, till she wished the earth might swallow her. Some women even stabbed themselves to death when they were given to an old man against their will; but in spite of all, the Tiv did not care.

The second level of violence comes when members internal to the Lele community break it’s own logic with violence. The only time when a human life is seen as fully tradeable to goods is when a man sells his claim on a woman to a tribe which has the means to violently cease her by force:

Sometimes when two clans were disputing a claim to blood compensation, the claimant might see no hope of getting satisfaction from his opponents. The political system offered no direct means for one man (or clan) to use physical coercion or to resort to superior authority to enforce claims against an other. In such a case, rather than abandon his claim to a pawn woman, he would be ready to take the equivalent in wealth, if he could get it. The usual procedure was to sell his case against the defendants to the only group capable of extorting a pawn by force, that is, to a village.

The man who meant to sell his case to a village asked them for 100 raffia cloths or five bars of camwood. The village raised the amount, either from its treasury, or by a loan from one of its members, and thereby adopted as its own his claim to a pawn.

Once he held the money, his claim was over, and the village, which had now bought it, would proceed to organize a raid to seize the woman in dispute.

In other words, it was only when violence was brought into the equation that there was any question of buying and selling people. The ability to deploy force, to cut through the endless maze of preferences, obligations, expectations, and responsibilities that mark real human relationships, also made it possible to overcome what is otherwise the first rule of all Lele economic relationships: that human lives can only be exchanged for other human lives, and never for physical objects.

The third and most total level of violence is when outsiders hijack the Lele logic with violence. In other words, when the market economy is introduced to human economies.

By the height of the trade fifty years later, British ships were bringing in large quantities of cloth (both products of the newly created Manchester mills and calicoes from India), and iron and copper ware, along with incidental goods like beads, and also, for obvious reasons, substantial numbers of firearms.19 The goods were then advanced to African merchants, again on credit, who assigned them to their own agents to move upstream.