Context

Thomas Hobbes was in the era of the English Civil war when he fled to France. He worked as Francis Bacon's secretary and engaged in dialogue with Galileo and Descartes. These events greatly affects his philosophical views. It's truly fascinating how the time one is in affects one's views (think how all the 20th century philosophers/artists/psychologists reference the bomb, something that barely crosses any of our minds anymore) as well as the caliber of thinkers one is surrounded with.

His chaotic time is why he values unity and stability so much more. Perhaps if he grew up in a tyranny it would be freedom which he advocates. Of course, after this unity is established, people would want more improvements. Perhaps the best we can do is only to make relative judgements/advice on how to proceed because there is no final state of utopia. This begs the question, how are our views trapped by the times we live in? How can we escape the confines of our time?

Title

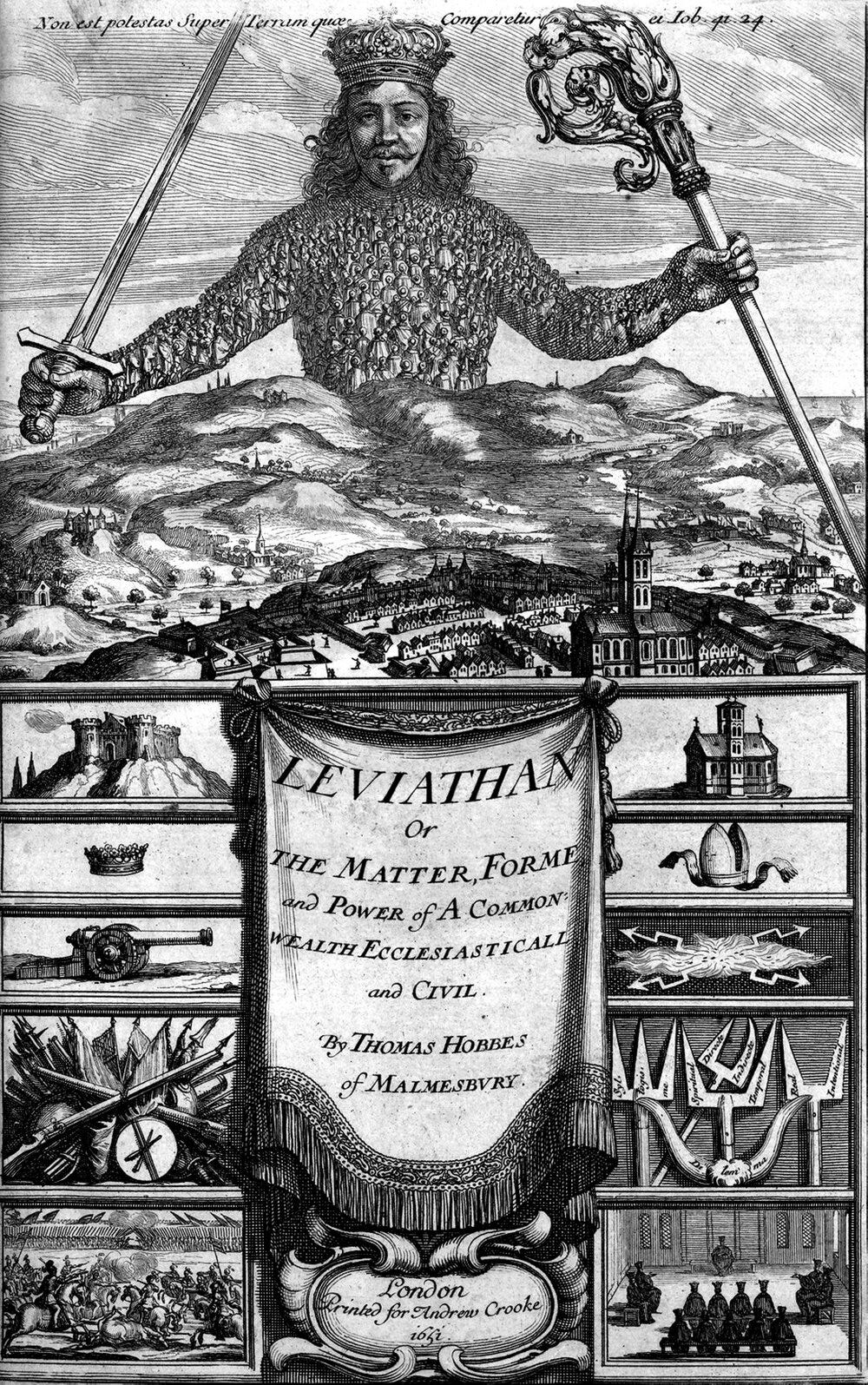

What's fascinating about Hobbe's book The Leviathan is the title he chose. This book is supposed to be a manual about how to bring about the divine good yet the Leviathan is a great enemy of God in the bible, one of the beasts of the apocalypse, if not the devil himself. "On earth it has no equal, a creature without fear. It surveys everything that is lofty: it is king over all that are proud."

One reading is that he is aesthetic and this was a revolt against religion, but there is also a protestant reading that the only thing which can prevent us -- fundamentally prideful creatures -- from destruction is this authoritarian, demon-like, force. The leviathan is the king over the proud, it needs to control our personal greed. Hobbes saw the purpose of the Leviathan as explaining the concepts of man and citizenship; he conceived of the work as contributing to a larger, three-pronged philosophical project that would explain nature in addition to these two phenomena.

On Epistemology

Hobbes disagrees with Aristotle on many things, not the least of which are his epistemic views.

He does not believe we experience some objective "essence" of external bodies. Instead all truth is consensus truth, constructed in some manner "Thus, since definitions, truth, first-principles and reason cannot be founded upon natural science, general consensus or a particularly enlightened person, Hobbes argues that there must be some agreed-upon judge or body that establishes such things. Truth for Hobbes, rather, must follow from consent."

"Hobbes' argument that all experience, and hence, all knowledge comes from sense can also be seen as an argument against innate knowledge, and for the tabula rosa (blank slate) model of the human mind." We can only talk about truth and reality buy buying into a coherent set of symbols and using our sense organs to refine them.

He defines fact from opinion: "When an argument does not begin with definitions, or moves improperly from step-to-step, its end product is but opinion."

It is thus not surprising that Hobbes praises geometry, a constructed and internally consistent logical system, as the prime epistemic model which he attempts to replicate in the social and political sciences.

On Man and the State of Nature

"The proper way to understand all men is to turn our thoughts inward and study one man (namely oneself), for to understand the thoughts, desires, and reasons of ourselves is to understand them in all mankind."

For every theory of political philosophy and good life you need to understand psychology and man because they are the basic building blocks. Just as how a good and coherent metaphysics and epistemology can influence your ethics. He moves in a very cartesian manner and is emulating geometry which shows just how much he is being influenced by the Scientific Revolution.

Hobbes encourages us to consider man in the state of nature, that is man without any cultural or political systems. He is not attempting to generate anthropological or historical insight but rather to propose a thought experiment to find the holy grail of "the human condition".

Hobbes takes a very mechanized way of viewing human nature: a machine optimizing ruthlessly for an objective function. He is both an ethical (man should solely optimize for their own good) and psychological (man left to his own devices does optimize for his own good) egoist. He conceives of the Hobbesian atomic individual who is in it for his own self-interest, which later lends to the construction of game theoretical explanations for morality.

I mean to an extent he is right that we optimize for an internal objective function. What appears to be for group selection is actually for individual gene selection. (But it's not that simple and may resemble more of a checks and balances systems which does not lead to the collapse into one sole function). However it seems that the best way to propagate is to cooperate and form this idea of ethics.

It is not a surprise then, under this egoistic view that "the life of man [is] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." Without contracts and obligations in nature, there is no justice. Everyone has a right to everyone else in the state of nature. And the equality stems from the fact that we have equal means of killing each other.

The state of nature is a state of war, this might not be explicit physical warfare but a form of passive-aggressive cold war. Three things causes quarrels: 1. competition for resources (roughly equivalent to Rousseauian amour de soi) 2. glory (roughly equivalent to Rousseauian amour propre) 3. diffidence, or fear of others taking what we have.

It is specifically this fear that leads us into civilization and makes us form bounds with each other.

The passions that incline men to peace, are fear of death; desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living; and a hope by their industry to obtain them. And reason suggesteth convenient articles of peace, upon which men may be drawn to agreement. These articles, are they, which otherwise are called the Laws of Nature: whereof I shall speak more particularly, in the two following chapters.

On Civilization

We are led through civilization, at least Hobbesian utopia, through guiding Laws of Nature who rest their authority on observation and reasoning. The first two, and most important, laws state our quest for self-preservation, and mutual castration of our liberties to enter into a contract:

Through reasoning that in the state of nature we are at war due to our quest for self-preservation, we discover the first fundamental law of nature, that man should "seek Peace, and follow it." The second fundamental law of nature derives from this first one, and states that we should lay down this absolute right of nature "and be contented with so much liberty against other men, as he would allow other men against himself.

Transferring this right to a mutually agreed upon power, namely, through a contract, follows from both laws of nature. You agree not to attack someone so long as they agree not to attack you, and both people transfer their rights of self-preservation to a common authority. A covenant is a contract made whereby one or more parties are bound to some future obligation (a contract can be a simple exchange of goods for services, which ends after the transaction ends).

From these first two laws of nature, Hobbes then deduces the third law of nature, "that men perform their Covenant made; without which, covenants are in vain, and but Empty words; and the Right of all men to all things remaining, wee are still in the condition of Warre." In other words, it is in our interest to obey our covenants, since the rewards for doing so (peace) outweighs the risk of breaking them (war). From this law of nature comes justice, so that to obey a covenant is justice, and to break it is injustice.

He further deduces a total of 19 laws which "is nothing else but the science of what is good, and evil, in the conversation, and society of mankind."

As a result, the Hobbesian state has this form of ultimate unquestionable authority and it can invade anyone's rights for the sake of stability.

On Liberty

Hobbes considers the nature of liberty under sovereign power and says that liberty means the ability to act according to one's will without being physically hindered from performing that act. Only chains or imprisonment can prevent one from acting, so all subjects have absolute liberty under sovereignty. Although the contract and the civil laws mandated by the sovereign are "artificial chains" preventing certain actions, absolute freedom and liberty still exist because the subjects themselves created the chains.

This is a very weak definition of liberty, but Hobbes still proposes it because he fundamentally believes that governmental authority lies in the consent of the people, therefore for you to form an authority, your constituents must be able to consent, and consent cannot happen where there is no liberty.

On Equality

For Hobbes, in the state of nature, Men do have equality, but it is an equality in the ability to kill each other. The differences in biological talents are neutralized by the same ability to rob it all away:

Nature hath made men so equal, in the faculties of the body, and mind; as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind than another; yet when all is reckoned together, the difference between man, and man, is not so considerable, as that one man can thereupon claim to himself any benefit, to which another may not pretend, as well as he. For as to the strength of body, the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination, or by confederacy with others, that are in the same danger with himself.

On Justice:

Justice necessitates some form of contract between two or more parties:

Where there is no common power, there is no law: where no law, no injustice. Force, and fraud, are in war the two cardinal virtues. Justice, and injustice are none of the faculties neither of the body, nor mind. If they were, they might be in a man that were alone in the world, as well as his senses, and passions. They are qualities, that relate to men in society, not in solitude.

On Religion

Fear serves not just as the driving force behind our desire for peace, but is also the foundation of religion. According to Hobbes, the natural cause of religion is anxiety of the future, which is furthered by ignorance of cause and effect relations. Religion comes from three sources: 1) curiosity into the causes of events; 2) curiosity of the causes of these causes; 3) forgetting the order of things and past causes and effects, which is then attributed elsewhere, i.e., Unfortunately, religion has been misused to make men obedient to a self-serving authority.

Not only does this offend true religion, since it is a perversion of proper religious doctrine, but this is also counter-productive to a society's well-being, as mismanagement and chaos are remain unchecked and run rampant throughout the public.

Importance

Hobbes Leviathan is important because it is one of the first text in western history to conceive of the validity and authority of government to rest in the consent of it's citizens. This is a huge shift from when power came from religion. Hobbes laid the groundwork for constitutional government by grounding the authority of the sovereign in it's subjects.

Furthermore, natural law originates from observing the behaviors of man not from Aquinian divine or eternal law. Covenants are now between man to man not from man to god. Both covenants and natural law, which have deep religious implications in the Judaea-Christian traditions have taken an anthropocentric shift.

Lastly, the Leviathan is also important because it thinks about morality in a different way. Whether it be Plato or Augustine, thinkers before Hobbes conceived of morality as duty, but Hobbes formulated as a right. The first fundamental law which states the "absolute right of nature" for self-preservation. Again we see a shift here from collectivist thinking (duty) to individualistic thinking (right).

The moral logic is something like this: nature has made individuals independent; nature has left each individual to fend for himself; nature must therefore have granted each person a right to fend for himself. This right is the fundamental moral fact, rather than any duty individuals have to a law or to each other.

Great post. Going back over your older posts, and Rediscovered this oldie. This may seem like a small detail to pick up on, but what are your reasons for thinking Hobbes' definition of Liberty is weak?