Companion lecture, Rousseau’s First Discourse:

Professor Kelly's Book (affiliate): https://amzn.to/4bX9JQD

My book notes: https://www.johnathanbi.com/p/rousseau-as-author-by-christopher

Introduction

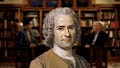

Johnathan Bi:

Superheroes have never been more popular in movies, yet real heroes have never been more absent in society. Who do we look up to today the same way Rome looked up to Caesar, that Christendom looked up to the saints. Nobody, because we tear heroes down and Rousseau thinks that's an existential threat to society. Christopher Kelly is one of the world's leading Rousseau scholars and today, we discuss the importance of heroes. Heroes aren't just ornaments, a nice-to-have, but the very foundations of community itself. What's worrying then is Rousseau's diagnosis that the modern world is hostile to heroes. It's not just we can't produce them, it's not just we can't sustain them, but that we are actively tearing them down. You're going to learn how many existential issues we face due to our lack of shared heroes. Issues as seemingly unrelated as the failure of reason in public discourse is due to the lack of heroic models. Without heroes, even reason is impotent. So what can we do? Can we bring heroes back? Rousseau doesn’t think that's possible anymore for reasons we'll explore, but he will teach us what the next best alternative to heroes are and how to live, if not thrive, in our hero-less world.

What is a Hero

Johnathan Bi:

Community can come only, only from something like a common identification with the same heroes. Why do heroes play such a constitutive role in Rousseau's political philosophy?

(Christopher Kelly, Rousseau as Author)

Christopher Kelly: Good. The idea of what a community is for Rousseau is a bunch of people who identify with each other in some important respect. And one of the most important media for that taking place is that they identify with the same thing.

Johnathan Bi: Same hero.

Christopher Kelly: Same hero in this case. So when Rousseau gives advice to Poland, where they wrote to him asking about forming a new government, he said you should reform the education system so that people aren't learning French literature and so on. They should learn Polish things. They should learn Polish history. And by the time someone is 12 years old, they should be able to name all of the Polish heroes of the independence movement against Russia.

This idea of one person identifying with another is extremely important for Rousseau. It's important in a general way because Rousseau places a great deal of emphasis upon compassion, which involves identifying with someone else, feeling their pain as your pain. It also is true in more complicated ways with the ways in which people develop vanity and pride and so on because they think about the way they look to someone else, which involves identifying with them.

In fact, Rousseau appears to be the first person in French to use the term "identify oneself with someone." Identification was used as a mathematical term, identity, the principle of identity, and it was used theologically when talking about the three persons of the Trinity as identical. But this idea of one person identifying with another just even grammatically never appeared in French before Rousseau's Second Discourse.

Johnathan Bi: We're going to spend this entire interview unpacking the importance of the hero for the community, but let's start from the basics. When Rousseau talks about heroes, who are the types of people that he has in mind?

Christopher Kelly: Mainly political leaders, people who perform great actions for the sake of the community. But it's also true, of course, that Rousseau is aware that there are dangerous or non-moral sides of people who we admire as heroes as well.

Johnathan Bi: Like Achilles.

Christopher Kelly: Yes. Yes, Achilles is one of the examples he gives. He wrote a discourse on the subject. The question that was posed was, what is the virtue most necessary for a hero and who are the heroes who lack that virtue? He begins by taking the traditional cardinal virtues, which he puts as courage, prudence, temperance, and

Johnathan Bi: Justice.

Christopher Kelly: -- and justice. And he goes through them one by one and denies that traditional cardinal virtues are things necessary for being a hero. And so he ultimately arrives at the idea that strength of soul is what makes a hero. And this is something that he takes most directly, he says, from Bacon. Strength of soul is the one thing necessary to make you independent of fortune. And then I think from that one can also trace it to Machiavelli and Machiavelli's notion of virtue. And you can see even from the formulation and the tracing into Machiavelli that --

Johnathan Bi: It's not moral.

Christopher Kelly: -- it's not moral, it's not justice. And courage is the traditional virtue that Rousseau spends the most time on, but he also suggests that courage is a rather morally questionable virtue. Rousseau says there are plenty of thugs who are courageous just --

Johnathan Bi: Nazi soldiers storming the front lines.

Christopher Kelly: Fanatics are courageous, and they're not necessarily heroic by being that. But he also argues there are examples of heroes who aren't courageous. You could be a general who doesn't have to be courageous in the way that a soldier on the front lines is courageous and still be a hero because he knows how to run a campaign. And the general is the one who gets credit for the victories and blames for the defeat more than the foot soldiers do.

Johnathan Bi: Right. What I want to emphasize here is that strength of soul, the actual unifying quality, let's call it that, of heroes is orthogonal to virtue. Now, there seems to be a flip side here where if you're weak-souled, you're easily tempted and you're almost certainly not virtuous. But the fact that you are strong-souled, that could lead you to do many different things. Being strong-souled is simply being effective. It's not about having the right ends. It's about being able to achieve your ends.

Christopher Kelly: Yes. And Rousseau talks about famous criminals who are strong-souled. But you raised the question about the relationship between strength of soul and virtue. Strength of soul is the source and supplement of virtue. So it's the -- you could say the precondition for virtue is the source of it.

Johnathan Bi: That sustains all the other virtues.

Christopher Kelly: And weakness makes us dependent, submissive, but also manipulative, bullying when we can be, and so on. So weakness and dependency are the source of vices. There are, he admits, criminals who are not weak, but he says those people you could reform. They could become something good. Whereas sort of hypocritical, weak, manipulative people, and his example of this is Cromwell. Oliver Cromwell is always presented, particularly in French fiction, as being this utter hypocrite that he pretends to be virtuous but is actually not at all and is, in fact, sort of cowardly, manipulative, and so on.

So Rousseau says that that sort of person is incapable of being reformed. You just can't make anything good out of them. Their weakness always will make them vicious. Whereas Rousseau talks about these criminals who have strength of soul as being capable of acts of generosity. And I think if you think about generous criminal types, this has become something which is very prominent in popular culture and was not really very prominent before the 19th century.

Johnathan Bi: Like the mafia boss who shares within his own family as one archetype.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. So we admire those people, right? We sort of. If you think about an example from the past of an admirable criminal, it would be someone like Robin Hood. But Robin Hood isn't really a criminal. He's really loyal to King Richard. It's the sheriff of Nottingham who's the criminal, right? It's not that Robin --

Johnathan Bi: But the Godfather is a criminal.

Christopher Kelly: The Godfather is absolutely a criminal, yes. It's a post-Rousseauian idea that there is a person who radically defies all of the conventions out of his independence of mind. And they're capable of terrible actions, but when we see them in movies and so on, we can't help but sort of like them. And I think this is the point that Rousseau is getting at. If weakness and dependency is what leads to vice, then strength of soul is what can lead to virtue. And in fact, Rousseau, when he sometimes identifies virtue with strength of soul, it's because he understands virtue as being controlling our desires, what we long for in the name of justice and this takes strength to do because it involves a certain renunciation.

Johnathan Bi: What I found fascinating about this admirable criminal archetype was I always attributed this to someone like Nietzsche. And I had to do a double take when I read your book to make sure I wasn't reading Nietzsche.

Let me give you a quote.

Rousseau states his preference for "lofty characters who bring even to crime an indefinable quality of pride and generosity" over "the vile and groveling soul of the [weak] hypocrite."

(Christopher Kelly, Rousseau as Author)

Of course, that's anachronistic, right? It's probably much more fair to say that Nietzsche was one of the people that Rousseau influenced with this idea, which is so interesting because we tend to think of Rousseau as this egalitarian figure.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. And I love reading Balzac. And in Balzac's novel Père Goriot, there is this wonderful super criminal who's a character who appears in a number of Balzac novels, and he ends by being head of the French police. He gets reformed. But he says, I'm a follower of Rousseau. I believe that we live in a completely corrupt order, which does not respect any part of the social contract. So I am an enemy of that order and anything it's in favor of, I'm against. So he's this criminal. He's a Rousseauian rejecter of an opponent of unjust conventions and institutions. And I think that that's in a way the most likely type of that criminal we tend to admire when we see them on television or in a movie or read about them in a book.

Johnathan Bi: I want to highlight another reason for why you suggested strength of soul is so important other than just being the foundation, the precondition for virtue.

I quote to your book:

[Rousseau is not] primarily interested in virtue, which can easily be shown to have an ambiguous status in his thought … what is fundamental for Rousseau is the experience of feeling one's own existence and that he endorses other things such as virtue, compassion, or freedom to the extent that they enhance this feeling … strength of soul, it might be said, yields a greater quality and quantity of existence to its possessor.

(Christopher Kelly, Rousseau as Author)

If that is true, the question I want to ask you is this: Does the hero who might have very little virtues except for strength of soul, does he actually live a better life than the wise man who has probably most of the virtues or as many of the virtues as humanly possible? From the Aristotelian perspective, you want to say no. We want to say that this is a much less virtuous life. But at the end of the day, everything bottoms out to the feeling of existence and the strength of soul is so important for that existence. Might our criminal archetype actually live a better life than your weaker souled wise man?

Christopher Kelly: Well, it's a very good question. It comes down to this question of goodness as opposed to virtue. And Rousseau is famous for saying man is naturally good. But of course people tend to think when they hear that, that he means they're spontaneously moral. But since he distinguishes goodness and virtue, that isn't what he means. And I think that what he means is two things in very simple language. One is they don't have any wicked dispositions. They don't take pleasure in doing harm to other people pointlessly. And secondly, that their experience of being alive is good.

So Rousseau's insistence is that at bottom, human beings are good in the sense that they are not wicked, denial of original sin, for example, and that they experience being alive as good. And of course, his critique of civilized life is very much that we have lost that experience. We live outside of ourselves. We're always not enjoying where we are now because we're thinking about where we would like to be in the future. We're not thinking about enjoying our existence because we're worried about what other people think of us. So we live outside of ourselves in the future.

We live outside of ourselves in other people. So both of those make our lives miserable. So the opposite of goodness is not wickedness. The opposite of goodness is unhappiness and wickedness. So we're unhappy. So the question then is who's the happy person? And what we were saying earlier about the hypocrites is they are miserable. They're wicked and miserable. They're always thinking about their security, getting something more, how they can protect themselves against somebody else.

Johnathan Bi: Because they're so weak, right?

Christopher Kelly: Because they're so weak and dependent. So weakness and dependence makes people miserable. A virtuous person is not miserable in that way because their virtue gives them a certain sort of independence. They're willing to not do the sort of dependent things that the hypocritical weak person would do. So the virtuous person is happier than the hypocritical wicked person most of the time. But he also says sometimes, in certain circumstances, virtue requires that you give up the things that are most important to you. And someone who does that can't be happy. A virtuous person in normal circumstances is happier than a wicked person, but abandoning the thing which you most deeply hold to in your heart for the sake of virtue --

Johnathan Bi: Doesn't make you happy.

Christopher Kelly: -- doesn't make you happy. And this is a great inspiration for Kant, this argument of Rousseau. But Rousseau doesn't abandon happiness as a result of this. He then raises the question, well, is there an alternative to wicked misery and virtue which is vulnerable to having to give up what you most love? And his answer is the wise man.

Johnathan Bi: So the wise man is willing to compromise his virtue to preserve happiness.

Christopher Kelly: Yes.

Johnathan Bi: I see.

Christopher Kelly: He may -- Rousseau says, would he be willing to give up the deepest longing of his heart for the sake of doing justice? And he says, probably not. And so he's good, but not virtuous. He's good because he has no desires that make him take pleasure in hurting other people because he has nothing to gain from it. You know, if he were in a situation of, you know, being out in the middle of the woods and starving and so on, there was only enough food for one person, he would take it for himself. But that's not willfully hurting other people.

Johnathan Bi: So the wise man is as virtuous as one can be without hurting his own, fundaments of his happiness. But what about my original question? The hero who is not as virtuous as the wise man, who has a surplus of strength of soul that gives him an increased feeling of his own existence. Doesn't that -- isn't that a better life, even if it's a less happy life?

Christopher Kelly: Well, I think heroes are people who are engaged in social life in a way that does involve some sacrifice for themselves for the sake of glory or something like that. So they're not quite as independent as they would long to be.

Johnathan Bi: Right. So let me try to summarize what you were saying. There's four different archetypes of person. The wicked person, non-virtuous, not happy. The virtuous man, he who is willing to sacrifice everything for virtue. Cato might be an example, right? For freedom, for freedom killing himself. Also not the most happy for obvious reasons. And then you have the wise man who tries to be as virtuous as possible without harming the fundaments of his good life. So this would be Rousseau. And then you have the hero who probably doesn't have as many virtues as the virtuous man or the wise man, but has such a strong soul that transforms into a strong sense of existence. So each of these three live a version of the best life. For Rousseau, the wise man, it's happiness. For the virtuous man, it's the maximum amount of virtue. And for the hero, it's the maximum feeling of one's own existence. Is that right?

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. The one qualification I would make is that it's not so clear to me that the Rousseauian wise man pursues virtue but doesn't let it interfere with his happiness. He pursues his happiness.

Johnathan Bi: Right. And insofar virtue builds to that.

Christopher Kelly: And virtue can be consistent with that, but it's not that he's looking for virtue as much as he can get. He's looking for virtue as much as will make him happy to have.

Johnathan Bi: Right, right.

Why Heroes are Dangerous

Let me read you a quote.

Public felicity is far less the end of the hero's actions than it is a means to reach the one he sets for himself, and that end is almost always his personal glory.

(Rousseau, Discourse on the Virtue Most Necessary for a Hero)

The real irony of all of this is that the hero, one of the most important archetypes in people for the community, doesn't really care about the community.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah.

Johnathan Bi: For its own sake, but as a means to the ends of his own glory. And this is probably right. When you think about classical heroes like Achilles, what does he care about? He doesn't really care about helping the Greeks. He doesn't care about defeating the Trojans. In fact, he goes off when he doesn't get his glory, he goes off and he pouts. That's the story of the Iliad. The hero who benefits the community the most doesn't really care about the community. An example I have in mind here. So I've spent a lot of time with both the Buddhist monastic community as well as the entrepreneurial community in San Francisco. And what I find so interesting is that the Buddhist, they genuinely care about compassion, about helping the world, but they have to practice in a monastery hold away from the world. So they don't end up helping the community that much.

Now, the entrepreneurs, they might claim they want to help the world. It's really like the heroes for their own glory. But to win their own glory, they have to build products and services for other people. And so, again, I find it that this odd paradox where the people who I, I've met, who are the most genuinely compassionate, do the least to help the world. And the people who I've met who are the most selfish, at least in the glory seeking sense, are the most helpful in the community.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. I mean, Rousseau looks at the glory that these people are seeking as being glory that they're going to get 200, 300 years from now. Their own good can be allied to the good of the community. Because what will get them glory, what will get them glory is to have been the founders of a community that was successful in prospering for centuries. So that's good for the community, but it's not, if you said to them, would you be willing to --

Johnathan Bi: Destroy the community?

Christopher Kelly: Would you be -- or well -- or would you be willing to set up that community but nobody knows that you did it, you get no glory, that's a tricky thing. A good American example of what Rousseau is thinking about with this is, Lincoln's Young Men's, Lyceum speech. He says that the generation that did the American Revolution and the next generation really felt that they were doing something by establishing a just prosperous community that would last. So their own desire for greatness was satisfied by doing that. But now, the founders are all dead. We are no longer connected to that revolutionary moment. Our community has been established. If you want to be someone who just does something great, the temptation now would be to do something that destroys that community that turns it upside down. If you're someone who really looks to achieve something great with this life and be noteworthy, just being the, you know, the 13th governor of your state is --

Johnathan Bi: Isn't going to do it right.

Christopher Kelly: -- isn't going to do it, so you'll do something destructive, he said, but that also means there's an opportunity for the person to preserve the community against the people who do the things to destroy it.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Christopher Kelly: Lincoln tries to show a way in which, in this circumstance in which we're tempted for the sake of our own renown to do something to undermine a couple of generations before, well, there is a way of preserving what they've done that could give you even greater reputation.

Johnathan Bi: I want to bring up another possibility of danger, which is when I imitate a hero, I exist outside of myself. Usually for Rousseau, that's quite a suspicious avenue. That's a suspicious drive.

Christopher Kelly: Yes. And in fact I think you can say that that from the standpoint of a natural human being, all social life is wrong. It makes people miserable and so on. And thinking about other people and imitating them, wanting them to imitate you and so on. And the term Rousseau uses frequently for this transformation from natural life to social life is denaturing. And denaturing sounds very bad. And it usually is when he uses the term. However, when he uses it in the social contract, he says, this is what a legislator or founder of a community has to do. He has to denature people because by nature we don't associate with each other.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Christopher Kelly: Right. By nature --

Johnathan Bi: A Positive socialization.

Christopher Kelly: -- yes. It does mean that imitation in Rousseau's view has got a negative side and it's also got a positive side. But we have to understand social life as being essentially a life that involves imitation, imagination, and so on. Things which are from a natural perspective, profoundly questionable.

Why Society Needs Heroes

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Let me read you a quote from your book.

The perception of the legislator's soul secures consent for his institutions and a disposition to follow them … It is this desire to imitate the great soul of the legislator that will make the people "good and upright" citizens, just as it was the desire to imitate Jesus and the saints that made good and upright Christians.

(Christopher Kelly, Rousseau as Author)

What's important to the Roman Republic is the character of the founder Brutus, and not so much the laws. What's important to the prestige of the Roman Empire is who Augustus was and his prestige. What grounds the legitimacy of America today is the character of the founding fathers. This is how central heroes are to Rousseau's political philosophy. That this is the primary mode of legislation through character and imitation and not through law and reason. Is that right?

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. Rousseau says that the tendency today in 1750 is to debunk the heroes in the past.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Christopher Kelly: To say --

Johnathan Bi: That's even more true today.

Christopher Kelly: -- and -- exactly. These were vices rather than virtues. These are myths. People really didn't do this. You know, George Washington and the cherry tree we would say today or something like that, but the tendency now would be to debunk them. There is a tendency to say all the things from the past were really terrible things, claiming to be good. And of course, we are terrible, but we're about to be good, right? And Rousseau says that he is willing to bend over backwards to give a good reputation to founders from the past. I would say the one qualification I would make is that in the case of Brutus, you know, this is not the Brutus who killed Julius Caesar, but the Brutus who --

Johnathan Bi: Founded the Republic.

Christopher Kelly: -- founded the Republic, and particularly when he was one of the first two consuls, his sons were convicted of or were accused of conspiring to restore the monarchy. And Brutus did not recuse himself from the case. He served as judge of their case and sentenced them to death. Brutus was a loving father. It tore out his entrails to do this to his sons, but he did it. So he's an example, but he does it in the name of the law. Our admiration for Brutus is he is the person who sacrificed what is dearest to himself for the sake of the -- this just political order and the law that represents it.

Johnathan Bi: But that is what grounds the law. It's his character that grounds --

Christopher Kelly: Absolutely.

Johnathan Bi: --and gives legitimacy to law and not the other way around.

Christopher Kelly: Right. You could put it this way, that intellectually we could understand the justice of the law, but emotionally, what grabs us is the example of Brutus. And that gives us the motive to be really attached to this legal system 'cause there's a Brutus that stands with it.

Johnathan Bi: And I wanted to build upon this drive for debunking heroes, which is obviously exaggerated today. I'm thinking back to, you know, people pulling down statues of Jefferson, for example, because he owned slaves. For Rousseau, that's not just a harmless political act that's tearing down the very structure, the very bedrock of a community to remove people of these heroes. Here's my question. When I think Rousseau, I think general will, I think citizens gathering round in rational debate, I think of a society that is transparent to reason, that operates on transparent political principles. How do we square that Rousseau who society is grounded on reason with the imitative Rousseau who sees society as grounded on the heroic imitation of great founders?

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. I think it's connected with what I suggested before. Why should you prefer the general will to what's good for you? Wouldn't you prefer not to pay taxes? You could say, well, I can see that it's good for society, that there be taxes, but I'm going to be a free rider. Rousseau doesn't think it's difficult for people to understand what is good for the community. The difficulty is to prefer what's good for the community to yourself. So rational discussion could get you to what's good for the community if you're willing to discuss that. Otherwise, what you're going to do is provide specious arguments for things that are just what you want or what your group wants.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Christopher Kelly: It's really back to sort of Socratic platonic question, why should we be just, right?

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Christopher Kelly: I think that in academic philosophical communities, it people are likely to say, if we could figure out what justice is.

Johnathan Bi: Problem solved.

Christopher Kelly: All solved. And Rousseau would say, no, that's where it begins.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Christopher Kelly: Right? Because why should you be just. Why should anyone prefer that? Since justice is going to involve doing things that are isn't good for them?

Johnathan Bi: This is how impotent reason is.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah.

Johnathan Bi: For Rousseau, where we need imitative exemplars who use reason to even start wielding reason. And I think Brutus, the Brutus who drove Tarquin out is a great example here. He was someone who rationally abided by the general will, sacrifice his particular will, his concern for his children, for the general will, for the good of the republic. But your point here is that the Roman Republic needed a Brutus.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah.

Johnathan Bi: For people who wanted to imitate him and wanted to imitate his ability to use reason to will what is good for all. So that's why these two parts are actually deeply conjoined and necessarily dependent.

Christopher Kelly: By identifying with Brutus, you feel the strength of soul it took for someone to do that. He must have been an extraordinarily strong person. So by identifying with his heroism, I get a boost to the strength of my soul because I feel what that strength must be like in some way. So the identification with heroic figures means that your soul gets elevated, made stronger. You don't become Brutus. But the ordinary citizen says, well, you know, I can -- in my personal life, I'm not going to kill my sons. Fortunately, I'm not in that situation. I'd like to think I do the right thing, but I can pay my taxes.

Johnathan Bi: Right, right.

Christopher Kelly: And I have the motive. I'm living up to the standard that's set by him. And it's not the standard that's the important, it's the identification and the admiration for him that allows me to do that.

Johnathan Bi: The interesting point is when we imitate a hero, it's not just their substantive qualities we take on like the understanding of justice, but we actually take on their strength of soul or we were able to borrow some of that. An example I have is not a hero, but one of my best friends. The reason I was -- the reason I had the courage to switch from computer science to philosophy in the first place, coming from an Asian household --

Christopher Kelly: Oh, yeah.

Johnathan Bi: -- it takes a great will to do it coming from an Asian household was because my friend had given up a much more lucrative and prestigious career and to come back to school to study philosophy. And it was through imitating him, his strength of soul as well as his actions, that I was able to make that decision myself. So that's kind of the sort of imitative of strength that --

Christopher Kelly: Yeah, yes.

Johnathan Bi: -- that they were talking about.

Why We Can’t Have Heroes in the Modern World

I want to move on now to the next set of topics, which is in your book you described the modern age as an anti-heroic age. Why is that?

Christopher Kelly: Well, admiring heroes can easily appear to be accepting authority outside of yourself. And it also means accepting being bound by tradition rather than being free of tradition. So you can say that modernity means liberation from tradition, not following authority. Rousseau doesn't really look at the imitation of heroes as accepting authority. It's not, they're the divine will or something like that, it's something different. But he thinks that the critique of heroes as authority and critique of heroes as tradition misses something that's very important. Modern politics is largely devoted to economic issues and forcing people to obey the law. And that's it. And that's many issues that we would like to think are important for making a good community are just absent from that.

Johnathan Bi: And what's absent from this mode of politics is art. Art necessarily is the medium that you need to translate these heroes through because it's not the reason you don't describe all the formal qualities of Achilles. You tell the story of Brutus, you tell the story of Achilles. One of Rousseau's interesting claims is that modern art has degenerated and it has made us both too social and not social enough. Why is that?

Christopher Kelly: Okay. This remark, it really comes from his analysis of the theater. Rousseau says, you go to the theater with your friends and you sit there looking in front of you, not at your friends, not talking to your friends. So you're all alone in a crowd of your friends. And I think, in fact, the experience of watching a movie on your cell phone while in a bus with headphones on, really is in a way what Rousseau suggests the experience of going to a theater generally is. So we think of it as being a sociable experience, but it's really an isolating experience. We also think it's sociable because we think by going to the theater, we develop our moral sensibility. We see plays that teach us a moral lesson. You feel sorry for the good person who suffers. You applaud the triumph of virtue in the end. And then you pat yourself on the back for being such a sensitive person and such a good person for feeling this way. And then you go outside into the real world and somebody calls upon you to do something. It's trouble. Going to the theater, that was fun. Rousseau says --

Johnathan Bi: Gives you an outlet, an easy outlet.

Christopher Kelly: Right. Rousseau says, it's a pure experience. So you have a pure admiration for the virtue that you see on the stage. In real life, it's never a pure experience 'cause there's always some trouble involved in being virtuous. So you think of yourself as being a wonderful person who loves virtue, who's devoted to the good things. You'll sign a petition, but you know your neighbor's in trouble, you're not going to do anything to help them out. It's a phony, sociable experience. It induces a sort of social conformism 'cause you go to the popular plays and things like this and you congratulate yourself for having the same opinions as the other people who went to that and so on. But it doesn't really develop a very thick sociable behavior towards other people.

Johnathan Bi: So Rousseau's view of art clearly is a hydraulic one rather than a formative one. That art provides a channel for energies. In the hydraulic metaphor, you know, if something, if the water pressure goes out one way, it doesn't need to go out the other rather than a, the more you view this type of art, the more you'll be formed into this type of person. If that's the case, then shouldn't we watch bad media? Shouldn't we play violent video games? Shouldn't we watch pornography? Because then we can outlet all of our bad vices without getting formed. So it seems like Rousseau is kind of stuck here. If you think that art is hydraulic rather than formative, then just watch bad media. If you think it's formative, then watch good media.

Christopher Kelly: If you live in a society in which, if people aren't in the theater, looking at the theater, they're doing bad things, they're picking someone's pocket, they're seducing their best friend's sister, better they're in the theater, whatever they're watching. He said in Paris, if I can get people to sit in the theater for two hours a day watching a play, it'll reduce the crime rate by 1/12. That assumes that crime is being committed 24 hours a day. So it's an exaggeration. But this isn't so incompatible with what you say. It doesn't go quite as extreme. But the theater, even when it's not terribly good and moral is good for a bad society because it takes the place of things that are even worse.

But there are other forms of art. Novels are different. Rousseau says with his novel, I see a family in the provinces gathered around after dinner reading the novel aloud. And the novel is about their life and what their life could be. It isn't about imaginary figures on the stage, it's something that they can see as a relation to their own life and will make them think we can be happy here living in this domestic situation. We don't have to go to Paris to the big city where the theater is. So there are different types of art which are experienced in different ways. The novel is not for Rousseau -- it's private, but it's, private among a group of people who read to each other.

The first time I read Rousseau's novel was reading it, and it's 700 pages long. My wife and I read it to each other last thing at night, and it took us three months to read it. But we did it. We tried to reproduce the experience of Rousseau's readers. Now the novel isn't exactly for forming citizens. That's a domestic union, but Rousseau is interested in things in which people are active rather than passive observers.

Rousseau's mother, when she was young, was arrested for dancing in public in Geneva, and Rousseau is a great defender of dances. When he condemns the theater, he says, but you'll say, well, what entertainment if right for a republic? And he says, dances. People go to dances. They listen to music. They see each other. They're engaged. They're watching the old people watch the young people dance and remember when they were young. And the young people are dancing under supervision of adults, but they're getting to know each other and seeing who's attractive. The greatest Rousseauian novelist is Tolstoy, not Rousseau. In War and Peace, nothing good happens in a theatrical situation. Something good always happens when there's a dance or a ball, and it's a very Rousseauian point. So Rousseau is a great defender of activities that are genuinely social activities. I think one aspect of Rousseau's attack on the theater when he is writing to Geneva is not related simply to the theater, but it's being guided by French cultural imperialism.

If you're going to watch plays in Geneva, what plays you're going to watch? You're going to watch Mollier, Racine, Voltaire, because Geneva's a town of 23,000 people. How many great playwrights are there in Geneva? Name a great Genevan playwright. There aren't any. Rousseau also suggests, well, is Geneva really a place that has got a lot of great dramatic opportunities? They're watchmakers, they're engaged in commerce. It's not really -- there isn't a Genevan political life that's like the political life of Athens. I can give a contemporary example. There still is a law for Canadian television, had to have a certain percentage Canadian content, because if they didn't have that law, it would be all American shows. And it was thought, this is American cultural imperialism. We want Canadian content.

But what was the Canadian content? The problem was coming up with Canadian content that wasn't simply imitating American content. There was, I remember, a series called The National Dream. The National Dream was to build a trans-continental railroad. They did it. It's been fulfilled, so there's nothing left for us to do as Canadians. You need to have sort of a heroic history to have your popular culture tell your story in that way in a play, in a public media or television or movie. And it's not easy to do that everywhere, and particularly in very good, just communities that have a good social safety net.

Johnathan Bi: That didn't have a lot of turmoil.

Christopher Kelly: Where's the turmoil there? We have a TV show about not joining the American Revolution. That wouldn't be that exciting. It's hard in a community. There you could say that Rousseau's novel with the domestic setting and reading to each other and so on would be a more promising sort of thing to do.

Johnathan Bi: Best you can do. I want to zoom out and discuss another reason why it's hard to have heroes in modernity. And this is very unintuitive, which is that our language itself has declined. Language used to be poetic, persuasive, and now language has become too rational. Tell us about the decline of language and its political consequences.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. You can't really understand Homer and the power of Homer and the Greeks unless you understand that the poetic language of the Homeric epics is really song language. The word for law in Greek Nomos also is the word for tomb. And they didn't see a distinction. Some biblical language is that way. The Psalms can be sung. And so Rousseau insists that early languages and particularly early languages in southern climates had this musical character. Music, when Rousseau was young, was considered by people who wrote about it to be sort of the lowest of the fine arts. That visual arts are much better than music. What music can do is imitate sounds. Well, sounds are just not beautiful things. They're not the subjects that are in poetry. And Rousseau says, no, music isn't imitating sounds. It's using sounds to imitate feelings. And so when you listen to music, the experience is one of feeling. And that's what all the arts really are about. They're about feeling. And music then becomes the highest one because, we --

Johnathan Bi: Directly.

Christopher Kelly: -- anyone can understand that music makes them feel a particular way when they hear a song. When you hear a march, you can't not walk that way when you're walking. And a lot of post-Rousseauian modern art, visual arts is an attempt to stimulate feelings in people rather than represent the beautiful nature. Rousseau really elevates music from near the bottom of the hierarchy of the fine arts to the exemplary fine art. That's what the other ones all want to be, is music. And that influenced musicians and it influenced other artists as well.

But the reason it's so important as a social phenomenon is it's also very specific to the culture in which you grew up. So you grow up learning certain songs, and you're always attached to those songs. Somebody comes from another place and hears those, they mean nothing to them. He says there's a Swiss cow herding song that people from Switzerland, if they hear it when they're away from home, they immediately start crying out of homesickness. Anyone else hears it and they go, "eh". But now, in modern life, particularly through literacy, language has become much more influenced by writing than by music and by reasoning than by feeling. And then -- so it's lost a lot of the expressive power and music has lost some of the expressive power as well.

Johnathan Bi: And I see this in classical Chinese and modern Chinese where classical Chinese is deeply poetic, but it's very ambiguous, very difficult to learn. Modern Chinese is analytical. It's rigorous, but it loses the mystical force. And so what you're saying is that Rousseau paints a spectrum. On one extreme end, there's music, and this is maximum feeling. The other extreme end mathematical logic, maximum rigor, abstraction, reason. And that this degeneration of language means that when we communicate in political life, we're focused a lot more on reason, a lot less on feeling. But the issue is, and we've developed this already, reason is impotent.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah.

Johnathan Bi: So reason doesn't really work. This is what I found to be the most alarming conclusion of your book.

[After the philosopher's] attempt to purge Greek of its persuasive power, Rousseau argues that tyrants were quick to take advantage of the lack of "fire" that came from the rational enfeebled language … in political life persuasion, even with all its dangers, is the only alternative to coercion.

(Christopher Kelly, Rousseau as Author)

The idea is, if we don't have musical force, if we don't have feeling, if we don't have persuasion, rhetoric, art heroes, reason is impotent. The only thing that we are left with to govern society is either through material self-interest or physical force and violence. We've degenerated and deteriorated because our language has become more rational. Is that right?

Christopher Kelly: That's right. Something connected with fanaticism can be good for a community. At the same time, he's extremely aware of the dangers of fanaticism. He thinks that his contemporaries like Voltaire, for example, underestimate the force of fanaticism in the face of argument. And they also underestimate the possibilities for channeling fanaticism to good purposes. But that doesn't mean that Rousseau is any less aware of the dangers. In fact, he argues that European intellectuals who laugh at the Quran when they see it translated and say, how can anyone take this seriously? And he said, but if they actually learned Arabic and heard it chanted, these same people would be down on their knees worshiping. They're dismissive, but also vulnerable to the appeal at the same time because they don't understand what the appeal is. So Rousseau is very well aware of what the nature of the appeal is and but also is aware of the danger.

Johnathan Bi: In addition to the decline of language as well as art, another issue with modernity and heroism seems to be equality. Heroes naturally seem to be anti-egalitarian. The classical heroes were literally demi gods. That's another big issue with heroism and modernity, is it not?

Christopher Kelly: It is. And Rousseau, of course, is a famous egalitarian, but not entirely. This discourse on the origin of inequality, he shows a progress of a certain form of inequality, which he thinks is just simply pernicious. So he is a great defender of equality in that respect. But he has a note near the end of the Second Discourse in which he discusses distributive justice, in which he suggests that it's really important for a community to be able to give honor and rewards to good behavior. He suggests that Poland should set up a system in which at every moment of everyone's life, they're involved with a competition with everyone else to get honor. He argues the first thing you need to do is to get rid of serfdom. And you can't really abolish it overnight. But what you need to do is to have a way for serfs to, by their good behavior or something like that, earn freedom and a certain percentage freed every year.

Then when you become a citizen, you get elected to office but you're not eligible for a higher office until you've served in a lower office. You go through this sort of step system in which in Poland has got an elective monarchy, so you can get elected king. So you're always seeing above you the next step that you can rise to. The problem is when you get to be king, you're at the top. But we have to have it so that several months after a king dies, his reign is put on trial, and a decision is to be made as to whether he's to be buried with honors and his children are given certain privileges or whether he's to forever --

Johnathan Bi: So even the king has something to look forward to.

Christopher Kelly: -- forever put -- yeah. So even the king has to look forward to a public judgment about him that elevates his status after he dies. And so there you can say, this is profoundly inegalitarian, but Rousseau, since he insists that social life is involved in imitation and comparison with other people, an imitation in comparison with people always leads to a desire to be on top in the comparison. And...

Johnathan Bi: That's just a fact about social life.

Christopher Kelly: Sometimes people will say, well, you can get out of this dynamic by a sort of recognition of each other's dignity. There's an egalitarian way of solving this problem of pride in wanting acknowledgement for others. We all acknowledge each other as equals, and Rousseau, I think, does not believe that.

Johnathan Bi: Another way to frame response as an answer to my question of the challenge of egalitarianism that poses for heroism, is to state that Rousseau probably thinks the egalitarians who reject any form of heroism outright is a bit naive because in Rousseau's own designs, he does create these structures of competition avenues for potential heroism. Here's the last thing I want to explore on the challenges of heroism in modernity. I'm curious if Rousseau brings this up, but I think that one of the greatest threats to society today are memes, like internet means.

Because it takes away any basis for sincerity with such a low amount of effort, you can create an ironic depiction of something that removes it from any genuine desire or sincere conversation. Another phenomenon here is how much of our news is communicated through comedy these days? People like John Stewart, all those late-night comedy shows. Is humor and irony something that Rousseau picks up on as one of the reasons we can't have heroes anymore?

Christopher Kelly: Well, Rousseau is not against humor as such, but the proper response to injustice is anger, and humor makes you laugh at it, which makes you more tolerant of it in a way. If you think of someone like John Stewart and so on, it's sort of an angry humor. And so he could defend himself and say, there's plenty of moral indignation in my humor, but I think most people would say it's sort of less funny when it's that way. So laughing advice, Rousseau suggests, is only a step away from tolerating it. So humor is from the standpoints of moral virtue, a problem.

Johnathan Bi: Anesthesiac.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. Rousseau is not against irony in a classic sense. In fact, he thought it would be a good thing to add a new punctuation mark to French to indicate irony, which in a way destroys it being irony, but people do sort of telegraph their irony when they're being ironic.

Johnathan Bi: Tone of voice. Yeah.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. Satire is not really, it's got a minor place in Rousseau's thought, not a, I don't want to say he dismisses it altogether, but it's a minor place. He's not swift.

What are the Alternatives to Heroes

Johnathan Bi: So obviously the next immediate question is, what do we do without heroes given how central heroes are to political life, in the modern world? Rousseau gives us two substitutes for the hero, Emile and Julie, who are both these fictional characters. Tell us about Emile. How is he like and not like a traditional hero, and why is he a valid substitute?

Christopher Kelly: Emile is raised to be independent and free in a way that a normal citizen isn't supposed to be. So Emile does not get exposed to heroic literature when he is young and when he's older, he reads Plutarch and so on. But essentially, he criticizes Plutarch's heroes. He sees their flaws more than he sees what's great about them. Rousseau says if he just once wants to imitate anyone, if even if it's Cato or Socrates, all is lost. So no imitation. There is one case in Emile in which Emile is said to have a hero, however, and that is, he reads Robinson Crusoe with the rigamarole, taken out some of the rigamarole is that Robinson Crusoe was a slave trader before he was shipwrecked. And that's left out. He is shipwrecked, he's a man who lives by himself on a desert island.

And for an adolescent, the idea of living on a desert island is much less horrifying than it is for me. But it's so neat the idea you're there by yourself and you can take care of yourself, and you figure out how to do all these things and you build this wonderful fortress and raise goats. And so it's an example that Emile's imagination can get really engaged in, but it's his situation, Robinson's situation rather than his character that's important to him. So when Emile is in social relations, he thinks will this fancy lace shirt be of any use on the island? No. So I'm not interested in it. So it gives him a non-social standard to resist social temptations. It's interesting that it's necessary though he needs to be able to imagine being someone else. And I think...

Johnathan Bi: Even his independence is imitative.

Christopher Kelly: Yes. But it's not imitating Robinson as a hero though. He's said to be his hero, but immediately upon saying he's his hero, it's that he questions what he does and thinks of how he could do it better. Which isn't the way you think of Achilles. How could I kill people better than Achilles did?

Johnathan Bi: One thing you didn't mention, but you did mention in the book that's interesting is Emile does not have a desire for glory, for participating in the community directly. I think sometimes out of duty or out of an enlightened self-interest, if I want to protect my family, I have to defend this larger family, so even his interactions with the community is somewhat, it seems like transactional. Emile is almost the modern cosmopolitan globalist, who's independent, who strives to be self-sufficient, who interacts with communities in a somewhat transactional way, and let me see if I understood what Rousseau is getting at here. In Sparta, in a proper community with proper heroes, with proper morals, you want the person to be social. In today's day and age, if you cultivate a child who's too social, they're going to be an influencer, they're going to go on reality TV shows. It's the corrupting force of modernity that makes the best possible life possible.

Christopher Kelly: Yeah.

Johnathan Bi: Emile, someone independent. So Emile is going to be much less desirable both to the community as well as a life than someone like a Spartan king, but this is the best you can do in corrupt modernity. Is that right?

Christopher Kelly: Yes. He's trying to show what it means to think about whether you can be a free and independent individual and also be in good relations with other human beings, so that's the investigation that's involved. So Emile is raised for himself to be free and independent, which means not weak, hypocritical, and so on. He has strength of soul, but as you say, he's also not interested in glory, so he doesn't have the motive that a heroic legislator would have for getting involved in politics, in fact, what does motivate the young adult Emile is love.

Johnathan Bi: It's a private interest.

Christopher Kelly: He falls in love with Sophie and courts her and gets engaged to her, and he then is sent out to learn about politics. He travels around Europe to figure out where his family should live. He learns all the places in Europe are corrupt, and so he might as well live back home, but he's learned about politics from doing this. He is a sort of cosmopolitan in the sense that he's traveled around a lot, he's compared all these things, but Rousseau says that he makes friendships with people so that he can go back home and have them write to him candidly about what they think about his community, so his cosmopolitanism is all leading him back home, it's not...

Johnathan Bi: So he does care about his own community for its own sake or...

Christopher Kelly: Not for its own sake, no.

Johnathan Bi: Only for this enlightened self-interest, right?

Christopher Kelly: It's only... Yes, it's that he is going to have a family, and now, he has to use (indiscernible) 59:59 to fortune, he's got a wife and children, and so he is going to try to make sure that life is as good for them as possible in the community. That means he's going to have to be a good citizen in the way in which a normal American would understand, he'll go to community meetings, he'll do things like this. Rousseau suggests that if you get called upon to do some major public service, you should do it, but he also says, if you have too much integrity, they won't want you to do anything.

Now, interestingly, in the sequel to Emile, his family falls apart, he ends up a slave in Algeria in a stone quarry and leads a slave rebellion. Now, he doesn't lead a slave rebellion out of his principled opposition to slavery, he leads the slave rebellion because he and the other slaves are being worked to death, and they are going to die --

Johnathan Bi: It's again self-interest.

Christopher Kelly: -- unless they can get freed. The rebellion sort of fizzles because the speech he gives is, look, we're going to die, we've got no choice, we have to do this, it's a very rational speech, but what happens is the slaves are from different communities. And as it starts to fizzle, they start getting in a rivalry with each other. We Italian slaves, we're not going to give up the way the Greek slaves do and the Greeks say, oh, we're going to out do the English slaves, and then they end up being successful out of a national pride, which is something that Emile himself had not felt or been able to appeal to.

Johnathan Bi: So it's the limitations of the type of --

Christopher Kelly: So in this desperate situation, these emotional national ties are crucial for the slave rebellion being successful, and I think it shows a limitation of not of him as a human being, but him as a political leader, he doesn't understand quite, or have the capacity to do what's necessary in those situations.

Johnathan Bi: Right. Well, let's talk about another major example of a potential hero, or in this case, heroine, for Rousseau. And that's Julie. And I think for most of our audience, she will appear even less of a hero than Emile is. So tell us about Julie.

Christopher Kelly: Julie is wonderfully attractive, a spontaneous, sensitive, good human being, wonderful daughter, and so on. So she's an alluring character, but she has this weakness, she falls in love with a man that her parents forbid her to marry, and she's seduced by him, he goes off, and she ends up getting married to someone else in an arranged marriage, and her former lover comes back and she stays a loyal wife. She can't be considered to be a model of virtue because of being seduced, and on the other hand, Rousseau does present her as someone who is...

People can't help but want to be with her. She just has this magnetic personality, and furthermore, her fall from virtue, which is not the way Rousseau looks at it, but her having sex with her lover is something understandable in a young person living in this repressive environment, and then she leads a life that can't be reproached later on. So it was both an immensely popular and immensely scandalous book at the same time. Mothers were a little reluctant to have their daughters read it because it suggested that premarital sex isn't such a bad thing, and so it gives a picture of someone who is both weak, but also, I don't like to use the word charismatic, but magnetic personality.

Johnathan Bi: Where does that come from? Because so far, we've associated strength of soul to ability to inspire imitation, but Julie is weak, so where does her ability to inspire come from?

Christopher Kelly: Yeah. He refers to her as a beautiful soul. She's just so sensitive and outgoing. There's something about her soul which just pours out, so there's a sort of exuberance that's there. It's not strength of soul, like Lucretia in his play that he didn't finish, but I think Lucretia, his thought about that character turns into Julie, someone who's not this example of extraordinary Roman virtue that involves suicide to someone who's within reach of a modern character and therefore in some ways weaker, but the expansive-ness of her personality, I think is the thing. So she's a large figure, a larger-than-life figure, and everyone can't help but feel this in her.

Johnathan Bi: Right. How does that express? I'm still having trouble putting my finger on it. How does this expansive-ness, the larger... Is she really funny? Is she very kind? Does she make you feel like...

Christopher Kelly: No, I think it's her sensitivity and that's the role of compassion in Rousseau, because this identification can be identification with something strong that we admire and feel ourselves becoming strong when we experience it, but it can also be a feeling of identification with suffering, and a sort of sensitivity. And Rousseau suggests that in its most primitive form, it's just a terrible thing 'cause you're feeling the fear and pain that someone else is fearing, and that's why if you're compassionate and that way you want to run away whenever you see suffering.

But there is a way that a more developed compassion can be... You on the one hand, feel the other person's suffering and you want to do something for them, on the other hand, you feel I can do something for them, which shows I'm both not suffering, and I can take pride in that. The person who's suffering can feel condescended to if that's not done in a sensitive way. They also can feel irritated if someone doesn't identify what they're suffering, it dismisses it, belittles it. So compassion is a tricky thing, and Rousseau explores every aspect of it wonderfully, I think, but Julie is a compassionate person, she feels along with other people.

Johnathan Bi: Right. And this might be a direct sense of larger than life, in that compassion extends your being into others.

Christopher Kelly: Yes.

Johnathan Bi: In the same way that the hero does, but through a very different means.

Christopher Kelly: Yes.

Johnathan Bi: But it's all through this ability to, as you said, identify. That's the common strand here. So this is my final question, the fact that Rousseau would elevate Emile, this sort of self-sufficient, enlightened self-interest archetype as well as Julie, a beautiful but weak soul, is a pretty pessimistic diagnosis on modern life, in modern political life, is it not? Is there any way out so to speak?

Christopher Kelly: Well, I don't know there's a way out, there's a way in. What both of them share is they're both extremely compassionate. Emile when he's courting Sophie, one time he doesn't show up, and it's because he's come across a man with a broken leg and he's helping him out and he explains to Sophie, I love you, but I have this respect for human suffering and need to do something about it, and that's more important to me. And at that point, she realizes she's in love with him, 'cause this is the sort of man she wants. The family constituted around love and respect of the husband and wife for each other, and then their children is regarded as the bridge from individual life to social life.

If you wanted to say sort of Locke with his emphasis upon acquiring property and so on, is the inventor of bourgeois society, Rousseau is the inventor of bourgeois society, understood as the nuclear family devotion to the community because of the desire for the family to live in a good environment and compassion towards fellow citizens, so it's his addition to earlier modern thinking is love and compassion are two things which are feelings that we modern people can feel. Their individual feelings that are also have a social dimension or can be built upon to have a social dimension.

Johnathan Bi: Right. So maybe it's not that pessimistic after all, maybe this is an alternative route to create community instead of strength of soul and emulation identification through the great man, through the hero. It's compassion. That's the other way.

Christopher Kelly: Right. It's not political in the same sense, but it's a social development of certain social virtues that then can conceivably have political consequences.

Johnathan Bi: Right. Thank you, professor. Thank you for a fascinating conversation.

Christopher Kelly: My pleasure, John. Thank you.

Selfish Heroes Make Great Leaders | Christopher Kelly on Rousseau